Robbing the Bank

Image: CCHG

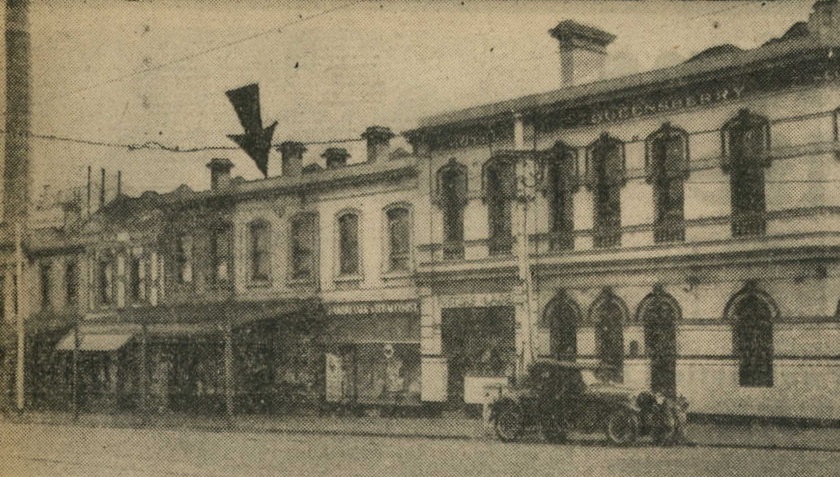

Former Melbourne Savings Bank Branch

208-214 Elgin Street Carlton

William Hardinge Wade was appointed acting Carlton branch manager of the Melbourne Savings Bank in January 1884 while the incumbent, George Meudall, took a leave of absence. Mr Wade, born in 1863, was very young to be a branch manager, but he had previously worked at the bank's head office and the commissioners must have been confident of his ability to take on the management role. Four years later, in November 1887, Mr Wade's prospects for a career in banking fell apart. He left his job without notice and an examination of the accounts revealed a defalcation of £289. This happened around the time of the Melbourne Cup and it was surmised that Wade may have run up gambling debts and fled to Sydney. A warrant was issued for his arrest and intercolonial police were alerted, but no trace could be found of him. 1,2

He was described in the Victoria Police Gazette as:

"A Victorian, a clerk, 24 years of age, 5 feet 5 inches high, slight build, square shouldered, very square shaped face (especially the lower part), fair complexion, freckled, light brown hair and small moustache only ; generally wore brownish tweed sac or paget suit and a light brown hard hat ; has a peculiar habit of fidgeting with the ends of his moustache, and he speaks in a nervous and abrupt manner." 3

In January 1888, the bank commissioners offer a reward of £100 (more than a third of the amount stolen) for information leading to the arrest of William Hardinge Wade. The conditions attached to the reward specified that the arrest must be made by 20 February 1888 if Wade was found within Victoria, or 20 April 1888 if he was found elsewhere. Despite the generous reward, William Hardinge Wade was never arrested and the bank's reputation may have suffered for having employed a criminally dishonest branch manager. 4

The Melbourne Savings Bank first opened a branch in Carlton in March 1882, under the management of George Meudall. For the first few years, business was conducted from a two storey shop building on the corner of Elgin and Keppel streets and, in keeping with bank practices at the time, the branch manager lived on the premises. In 1886, the Melbourne Savings Bank made a long-term investment in Carlton by establishing a new branch building that now stands on the corner site. The ornate two storey structure was built by Dunton & Hearden to the design of architect George Wharton. The Melbourne Savings Bank merged with the State Savings Bank in 1912, which in turn was taken over by the Commonwealth Bank in 1990.5,6,7

For more information on banks and banking in Carlton, read our November 2021 newsletter.

1 North Melbourne Advertiser, 25 January 1884, p. 3

2 The Herald, 12 November 1887, p. 9

3 Victoria Police Gazette, 16 November 1887, p. 326

4 Advocate, 21 January 1888, p. 11

5 The Record, 3 March 1882, p. 2

6 Australian Architectural Index, Record no. 79186

7 https://researchdata.edu.au/state-bank-victoria/492629

Photo: CCHG The Shooting Scene 24 Shakespeare Street North Carlton  Photo: CCHG Scene of Alleged Knife Attack 18 Murchison Street Carlton

Notes and References: |

Shooting in Shakespeare Street

|

Photo: CCHG Mallow House 50 Dorrit Street Carlton

Notes and References: |

November 1949 |

Photo: CCHG The Beaufort (Former Clare Castle Hotel) 421 Rathdowne Street Carlton

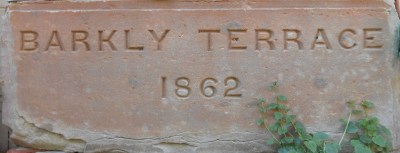

Image Source: Chronicle (Adelaide), 5 November 1927 50 Barkly Street Carlton "A sombre bluestone house"

Photo: CCHG Stone Lintel from Barkly Terrace A silent witness to the events of 27 October 1927

Photo: CCHG Right of Way, 33 Macarthur Place Carlton A Belgian revolver was found near the side fence

Photo: CCHG 12 Murchison Street Carlton Home of hire-car driver John Hall in 1927 |

Last Drinks for Squizzy TaylorThe Clare Castle Hotel, renamed The Beaufort in 2012 and now the Italian restaurant Capitano, has special significance as a hotel visited by notorious gangster Squizzy Taylor on his last fateful journey of 27 October 1927. The hotel, on the corner of Rathdowne and Palmerston streets, dates back to 1866 and was first licensed to John Ryan. The building later underwent extensive renovations, which were completed in September 1927, a few weeks before Squizzy's final visit. 1,2,3 Squizzy's last journey began at the Bookmakers Club in Lonsdale Street, where he and his two associates hired a car driven by John William Hall. Following Squizzy's directions, Hall proceeded along Exhibition and Rathdowne Streets to Carlton. Contemporary newspaper accounts differ in the location of hotels visited by Squizzy and his associates – Rathdowne, Drummond, Elgin or Lygon Street – and many other aspects of the case. According to Hall's statement at the inquest, the three men went into a hotel on the corner of Rathdowne and Palmerston Streets, and two other unnamed hotels in Drummond Street. 4,5,6 After leaving the hotels, they went to Barkly Street and Squizzy directed Hall to park on the right hand side of the street, near the intersection with Nicholson Street. And it was at Barkly Terrace, on the northern side of the street, where Squizzy was fatally wounded in a shootout with his rival John Daniel 'Snowy' Cutmore. No. 50 Barkly Street, one of five cottages comprising Barkly Terrace, was a boarding house operated by Snowy's mother Bridget Delia Cutmore. Snowy Cutmore was pronounced dead at the scene by local doctor Alan McCutcheon, from 88 Rathdowne Street, while Mrs Cutmore was wounded in the shoulder, but she survived. Squizzy, driven by John Hall, made it to St Vincent's Hospital in Fitzroy, where he died within half an hour of admission. On that day in October 1927, three people were shot and three firearms were involved. After Squizzy's death at St Vincent's, a pistol was found in his pocket, though his widow Ida stated that he was not carrying a weapon when he left his home in Richmond that morning. A Belgian revolver, believed to be fired by Snowy Cutmore, was found the next day by Mrs Hudson in the backyard of her home at 33 Macarthur Place South, just inside the fence adjoining a right of way. The third firearm, a Webley Automatic Colt revolver, was discovered by police in a lavatory cistern at the rear of 50 Barkly Street, but this was not made public at the time. Despite detailed ballistics evidence presented at the inquest, the coroner Mr Berriman was unable to determine who shot who, and an open verdict was returned. 7 Squizzy was buried in Brighton cemetery on 29 October 1927, accompanied by "a disgraceful exhibition of morbid curiosity, coupled with a callous disregard for the feelings of the bereaved". The funeral was arranged by Josiah Holdsworth of Lygon Street and local legend has it that the undertaker was never paid for his services. 8,9,10 Hire-car driver and Carlton resident John Hall, who was abandoned by Squizzy's associates and left with the responsibility of taking him to hospital, was probably also out of pocket. John Hall was living at 12 Murchison Street, a short distance from Barkly Street, at the time of the shooting. According to rate book and directory records, he lived there from 1927 to 1928. The house, which still stands today, was built in 1916 by Carlton builder W.D. Wilson for Sarah Wood.11 Snowy Cutmore was buried in Coburg cemetery and his widow Gladys stayed on at Barkly Terrace for a few years. Snowy's mother Bridget Cutmore lived there until her death in 1938, aged 70 years. Barkly Terrace, originally built in 1862 and described in The Sun as "a sombre bluestone house", was owned by Alfred Abraham Solomon and his executors from 1919 to 1940, and then by members of the Labattaglia family. In an ironic twist, Francesco Antonio (Frank Anthony) Labattaglia was the third husband of Squizzy's widow Ida Pender. They married in 1933, after Ida divorced her second husband George Lewin (aka Mickey Powell) in 1932, on the grounds of desertion. 12,13,14,15,16,17,18 Barkly Terrace survived its first hundred years, then it was placed under a Housing Commission order in 1963 and demolished in 1965. The "sombre bluestone house", as described in The Sun in 1927, was replaced by a block of flats. A stone lintel salvaged from the demolition site remains a silent witness to the events of 27 October 1927.19,20

Notes and References:

Related item: |

Photo: CCHG Scene of Robbery in 1917 (now Carlton Cellars) Corner of Canning and Richardson Streets North Carlton |

A Sweet-Toothed Robbery in North CarltonIn February 1917, just before Valentine's Day, two thieves managed to dodge police bullets and make off with 2,800 pounds of sugar, 112 pounds of rice and 15 shillings in cash. The well-planned robbery took place around 3.30 am at William Drum's licensed grocery store, on the corner of Richardson and Canning Streets, North Carlton. The two men had loaded up their horse-drawn cart and were about to make their exit when they were challenged by Constable Simon McKenzie, on patrol from the North Carlton Police Station and armed with a revolver. The horse and cart took off and Constable Simon McKenzie fired 3 shots at the horse, which would have been the 1917 equivalent of shooting out the car tyres. But the bullets missed their mark, as did the remaining 5 shots aimed at the cart driver. The thieves got away with their haul, valued at about £40 and most likely destined for the re-sale market. A search of Mr Drum's premises revealed that two locks on the front door had been forced open and the arc light in front of the store had been disabled. Surprisingly, two demijohns of whiskey, valued at £10 each, were left behind in the shop. Spare a thought for Constable McKenzie – instead of being hailed the hero of a thwarted robbery attempt, he probably copped a ribbing from his fellow police officers because he couldn't even shoot a horse and cart.

References: |

A Rogue and Vagabond

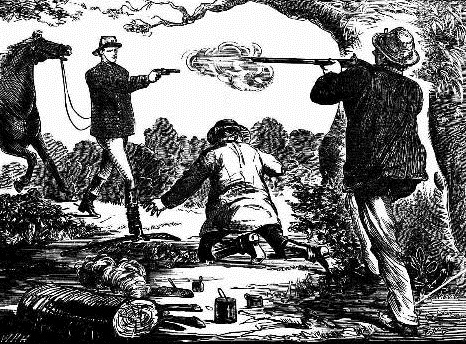

Image Source: Weekly Times, 17 December 1870, p. 9

John Sullivan (right) shooting at Mounted Police Constable Mays

What is the legal definition of frequenting a public place? This question was posed in Carlton Court in April 1887, when John Sullivan faced a charge of being a rogue and vagabond, and a suspected person frequenting a public place. Sullivan (also known as John Lewis, John Lewis Elliott and William Jackson) was born in South America in 1850 (or earlier) and worked as a sailor before embarking on a life of crime. He was imprisoned at Richmond stockade for nine months in 1864 on a charge of larceny. The following year, in June 1865, he served three concurrent sentences in Pentridge prison for burglary and receiving stolen property. During his time in Pentridge, he committed numerous offences, ranging from the seemingly trivial (talking and laughing ; having tea, sugar etc) to the more serious (fighting ; disorderly conduct). These offences added time to his sentence and he was finally released in December 1869.1,2

Sullivan may have learned a few tricks while in Pentridge, for he resumed his criminal activities and became notorious as the Yarra Flats bushranger. He evaded police for some time, then Sullivan and fellow bushranger, Charles Smith, were bailed up by Mounted Police Constable Mays in December 1870. Mays narrowly dodged a bullet fired by Sullivan – a charge that Sullivan was later to deny as accidental – but he succeeded in arresting Smith. Sullivan was eventually arrested further up the Yarra track and brought back to Melbourne to face charges of attempting to abscond, horse stealing and shooting with intent. In February 1871, he was sentenced to six months hard labour (in irons) on the first charge, eight years on the second and seven years on the third. His prison record describes him unflatteringly as having a swarthy complexion and a "face blotched with pimples". True to his form, Sullivan added to his sentence by committing various offences while in gaol, including a serious assault on fellow prisoners Roland Leigh and James Doolan, and a knife fight with former bushranger Captain Moonlite (alias Andrew Scott). In October 1884, having spent the greater part of the last twenty years in prison, Sullivan was once again a free man – though not for long.3,4,5,6,7

Less than two months after his release from Pentridge, Sullivan was back in court facing a charge of assaulting a man named George McLeish in Bourke Street, Melbourne. McLeish had just come out of a theatre when he was approached by two woman, one of whom was Sullivan's wife. Sullivan took exception to McLeish talking to his wife, even though she had initiated the conversation, and punched him in the face, knocking him to the ground. A passing police constable intervened and prevented the violence from escalating. When Sullivan appeared in the City Court a few days later on 17 December 1884, he admitted his prior convictions and begged for leniency, stating that since leaving gaol he had endeavoured to earn an honest living by keeping a small shop. He was sentenced to two months' imprisonment and would have spent Christmas 1884 in gaol. Sullivan and his wife were involved in another incident in April 1886, when he was found fighting with her in a city street and disturbing the peace in the early hours of the morning. Both husband and wife were taken into custody, but the court favoured Sullivan, who stated he was trying to take his wife back home, and fined her 10 shillings. At the time, it was reported that he had a shop in Collingwood and his wife assisted him in the business.8,9

The following year, 1887, was an eventful one for John Sullivan. In February, he was involved in an early morning fracas at the home of Mr Cousens at Ten Foot Hill, Castlemaine. An altercation took place between Sullivan and a man named Thomas Ray, who struck Sullivan on the forehead with a hammer, inflicting a severe wound. Sullivan retaliated and threatened to "knock Ray's brains out", when the potentially serious situation was averted by the arrival of police. The two men and Thomas Ray's wife Esther were charged with creating a disturbance. In Castlemaine Police Court on 9 February, Thomas Ray was fined £1, in default seven days' imprisonment, while Esther was fined the greater amount of £6, in default two months' imprisonment, for using obscene language. Sullivan was discharged and then immediately re-arrested as he left the court. Sergeant Nowlan recognised Sullivan's description from the Police Gazette and arrested him on a charge of larceny as a servant. He allegedly stole 15 plugs of tobacco, 4 shillings in silver and a pair of scissors from his employer, John Kelly, at North Fitzroy on 27 January 1887. Sullivan was remanded, at his own request, to appear at Fitzroy Police Court, where he would be in a better position to raise bail, set at £50, and two sureties of £125 each. On Monday 14 February, the court was told that Sullivan was an employee of John Kelly, a barber and tobacconist of St George's Road, North Fitzroy. Kelly had left John Lewis (as he was then known) in charge of the shop for an afternoon and, when he returned, he found that Lewis had decamped and the stated items were missing. But this must have been Sullivan's lucky month, for he was once again discharged, on the grounds that there was no evidence that he had taken the stated items.10,11,12,13,14

Two months later, in April 1887, Sullivan's luck had run out when he was arrested outside the Dan O'Connell Hotel, on the corner of Canning and Princes Streets, Carlton. He was allegedly the "lookout" for Robert McFadden, who had broken into the hotel with intent to commit a burglary. Nothing was stolen and Sullivan's initial charge was being an accessory before the fact. But his criminal past had caught up with him and the charge was subsequently altered to being a rogue and vagabond, and a suspected person frequenting a public place. His defence was dependent on the curious interpretation of a public place as being a street that led to "any river, canal, quay, etc.", as defined by the Colonial Act. Sullivan's defence counsel, Mr Leonard, argued that Canning and Princes Streets were not public places according to the Colonial Act definition. He cited the 1883 case of Benjamin Adams, who was arrested in Victoria Parade, Collingwood, on a similar charge and the conviction was quashed on appeal. On the charge of "frequenting", Leonard cited a case recently decided by the English Court of Exchequer in which being seen once in a street did not constitute frequenting. Leonard had done his research and prepared his case well, but the Bench was against him. They favoured the broader interpretation of a public place as being any street and frequenting as being seen one or more times in such a street. Sullivan was sentenced to one month's imprisonment and Mr Leonard, in fit of pique, reportedly said: "Hand me down my law hooks. I'll never take the trouble to hunt up law cases for this Bench again".15,16

What became of Sullivan after his release from prison? It is unlikely that he would have returned to work at John Kelly's barber shop and the publicity surrounding his criminal record, and his propensity for violence, would have discouraged most employers from taking him on. His Victorian prison record shows no further custodial sentences, however Sullivan was known by several different aliases and may have re-invented himself. He could have travelled, interstate or overseas, and established himself in a new town or country. Remember that he was once a sailor – what better way to escape your past?

Notes and References:

1 The Age, 28 April 1887, p. 6

2 Central Register of Male Prisoners, no. 7265, Register 10, p. 672 (VPRS 515). This record states that Sullivan was 19 years old in 1865.

3 Weekly Times, 17 December 1870, p. 9

4 Central Register of Male Prisoners no. 7265, Register 13, p. 298 (VPRS 515). This record states that Sullivan was born in 1850.

5 The Argus, 2 September 1875, p. 4

6 The Argus, 19 January 1876, p. 4

7 The Australasian, 1 December 1877, p. 1

8 The Age, 18 December 1884, p. 1

9 The Age, 19 April 1886, p. 6

10 Bendigo Advertiser, 10 February 1887, p. 3

11 Bendigo Advertiser, 11 February 1887, p. 3

12 Mount Alexander Mail, 11 February 1887, p. 2

13 Victoria Police Gazette, 2 February 1887, p. 40

14 Mercury and Weekly Courier, 18 February 1887, p. 3

15 Avoca Mail, 29 April 1887, p. 3

16 Mercury and Weekly Courier, 23 June 1883, p. 2

In recent years, many historic Carlton buildings – both private residences and business premises – have

been defaced with unattractive graffiti and tagging. Back in the 1980s, graffiti was not just a medium of

self (or selfish) expression. It was also used to communicate social, political and public health

messages. B.U.G.A.U.P. (Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions) was formed in

Sydney in late 1979 and soon became active in Carlton and other inner city suburbs of Melbourne. The

movement raised the ire of the tobacco, alcohol and advertising industries, resulting in prosecutions.

Two such cases were heard in Carlton Court in 1980. In February Dr Josephine Kavanagh, a radiologist

at Royal Melbourne Hospital and anti-smoking campaigner, was placed on a 12-month good behaviour

bond and ordered to pay $125 compensation to the Pacific Outdoor Advertising Company for painting

slogans on a cigarette advertising billboard. Six months later, in August 1980 two young women – a

medical student and speech therapist – appeared in Carlton Court to face charges for wilful damage in

defacing a cigarette advertising poster. The hearing attracted a group of about 30 anti-cigarette

advertising protesters, who demonstrated outside the court in support of the women. The case was

rescheduled to the Melbourne Magistrates Court and the women were placed on 12-month good

behaviour bonds and ordered to pay $106.90 each in costs.

References:

Australia was a conservative country in the 1960s and in October 1966 a drawing exhibited at Strines Gallery in Rathdowne Street, Carlton,

challenged acceptable standards of public decency. The gallery's director, Sweeney Reed, had an impressive art pedigree.

He was the son of artist Joy Hester and the adopted son of art patrons John and Sunday Reed.

The Reeds financed Strines Gallery, which Sweeney managed from 1966 to 1970.

Sweeney appeared in Carlton Court in February 1967 to answer charges of having exhibited an obscene article,

a black and white drawing entitled "Oops" by artist Ronald Upton. Upton was charged with having aided in the exhibition of an obscene article.

The Canberra Times reported that witnesses, including an Anglican bishop, a fine arts professor,

the acting director of the National Gallery and a psychiatrist,

attested that Upton's drawing was of artistic merit and would not injure or corrupt children or teenagers.1

Stipendiary Magistrate R.W. Smith adjourned the case for a few weeks. In March 1967, after viewing the drawing at the gallery and within the court room,

Mr Smith ruled that, while the drawing emphasised matters of sex and therefore fell into the category of obscenity,

it was of artistic merit and unlikely to deprave or corrupt the class of people who viewed the exhibition.

He dismissed the charges and ordered for the drawing to be returned to the buyer, Scott Stanley Carter.

Sweeney Reed, a brilliant but troubled young man, committed suicide 12 years later in March 1979.2,3

Sweeney Reed and Strines Gallery was the subject of an exhibition held at the Heide Museum of Modern Art, from August 2018 to February 2019.

The Bridget McDonnell Gallery, establised in Armadale in 1983 and in Carlton since 1986,

now occupies the former Strines Gallery site on the corner of Rathdowne and Faraday streets, Carlton.

References:

The young man had business to do at the Carlton branch of the English, Scottish and Australian Bank in Swanston Street.

He dressed carefully and checked his pockets to make sure he had what he needed before heading off.

On his arrival, he noticed that there were no other customers inside. That was good, the way he wanted it.

As he entered the bank, little did he know that Saturday 22 April, 1933, would be the last day of his life.

The clock on the wall had passed the hour and was heading towards the midday closing time.

The two bank staff – ledgerkeeper John Hayes and teller Andrew Frewin – were looking forward to knocking off and enjoying the rest of the weekend.

Hayes briefly looked up when he heard someone enter the bank, then returned to his book work.

Frewin was counting money inside the "teller's box", an enclosed work space with a metal grille that separated the occupant from the public area of the bank.

He saw the man approaching, but what happened next was so sudden and unexpected that Frewin had no time to react,

let alone defend himself. The man heaved himself onto the counter, reached over the top of the grille and grabbed a handful of bank notes.

Frewin felt a searing pain in his eyes and was temporarily blinded.

The metal grille, intended to protect bank employees and assets in the event of a robbery,

afforded no protection against a handful of pepper used as an offensive weapon.1

Hearing Frewin's cries of pain, Hayes instinctively reached for the revolver he kept under the counter.

He did not know the nature of Frewin's injuries, but he knew they had been inflicted by the man now running towards the door.

Hayes released the safety catch and fired a single shot.

Meanwhile, Mrs Ethel Halloran was shopping at Salvio's next door when she heard the commotion.

On entering the bank, she saw a young man lying on the floor, obviously in pain, and initially she thought he was a bank employee.

But he resisted her offer of help and pushed her roughly out of the way. She then realised that he was the perpetrator, not the victim, of a bank robbery.

She did her best to restrain him, but he managed to get to his feet and stagger out of the bank.

Mrs Salvio, who had followed Mrs Halloran into the bank, attended to Frewin and bathed his eyes in oil.

He had no recollection of what had happened after the pepper was thrown in his eyes, apart from hearing the shot from Hayes's revolver.

Hayes, still reeling from the shock that he had just shot a man, found a few bank notes dropped in the doorway, but saw no sign of the retreating robber.

Despite being shot in the chest, the bank robber managed to stagger two blocks before collapsing on the corner of Lygon and Queensberry streets.

He was found by Plainclothes Constable L. M. Coysh, who took him to the Melbourne Hospital.

On the way, the young man admitted that he had robbed the bank and asked Coysh: "Have you got the other fellow?"

He refused to give his name, saying: "Call me Smith", or the name of his alleged accomplice.

Was this an attempt on his part to divert police attention from himself as the sole perpetrator?

Within a short time, the answers to these questions were of no consequence because the young man died soon after admission to hospital.

The body of the mysterious "Mr Smith" lay in the morgue over the weekend until he could be positively identified.

His fingerprints, taken post mortem, showed that he had no record of any prior conviction in Victoria.

On Monday 24 April, The Age published a detailed description of the bank robber, issued by police:

About 24 years of age, five feet nine inches tall, medium build, clean appearance generally,

clean shaven, freckled face and hands, good head of auburn hair cut short back and sides;

rather thin face, prominent chin, flat nose with long bridge and showing signs of an operation to left nostril,

soft hands, giving appearance of not having done hard work for some time; long finger nails well manicured.

Dressed in blue suit with red pencil stripe, cream silk shirt, cream woollen fancy jacket, tan shoes with rubber soles.

On the shirt collar were faded letters S.K.Y.C. The trousers bore a cleaner's number. There was a scar above the right eye,

a scar on the right hip, and three prominent vaccination marks on the left forearm.2

The letters on the collar of the silk shirt provided a vital clue to the identity of the well-dressed and well-groomed bank robber.

"S.K.Y.C." were the initials of the St Kilda Yacht Club.

Mr John Stooke, commodore of the club, and Mr J.G. O'Neill, a member of the committee, identified the young man as a former employee of the club.

John Dickson (Dixson) had worked there as a cleaner and caretaker for about a year, and he was considered an industrious worker,

but he was dismissed in February 1932 for two incidents of insubordination. He had previously worked at Carlyon's Esplanade Hotel in St Kilda.

Once the identity was made public, other people came forward claiming to know Dickson.

Mrs S. Heal, a widow who lived in Queensberry Street near the bank, knew Dickson as a well-presented and well-behaved young Englishman.

He had visited her and her daughter regularly until about 12 months ago, when she thought he had gone to the country to try his hand at gold prospecting.

His reckless behaviour in robbing the bank seemed completely out of character with the young man she once knew. He had worked hard to send money back to England

to help his widowed mother and support his blind brother.3

Dickson's housemate, a farm worker named John McKenzie, had boarded with him in Dudley Street, West Melbourne, for about seven weeks.

The two men had known each other since 1927, when they had met at a training farm in Norfolk, England.

They had been trying find employment in Victoria and, in the week leading up to the robbery, McKenzie claimed that Dickson had said several times that he would have to get money from somewhere.

Somehow the image of Dickson as a farm worker or cleaner did not tally with that of the soft-handed and well-manicured man who lay on the mortuary slab.

Whatever he had been doing since he left his employment at the St Kilda Yacht Club in February 1932, Dickson had the means of maintaining his clothing and appearance.

This raises the issue that he may have owed money and was forced by circumstances – or his creditors – to rob the bank.

Once Dickson had been positively identified, police were keen to follow the line of enquiry that he had an accomplice.

Not all the stolen money (estimated at £40 in total) had been recovered from what was dropped when Dickson made his escape from the bank.

Several witnesses reported that they had seen him passing money to another man waiting outside the bank or nearby,

but there was insufficient information to identify the alleged accomplice. There was another possible, more prosaic, explanation.

Dickson was in a weakened state from the chest wound and he may have inadvertently dropped the money as he made his painful way from the bank

in Swanston Street to Lygon Street, where he collapsed. It was conceivable that a few stray notes were picked up and pocketed by passers-by.

Police were also trying to locate a friend of Dickson's, who was believed to work at a hotel in South Melbourne, but nothing came of their investigations.

The inquest was held on Friday 28 April, six days after the bank robbery and shooting. The Deputy Coroner, Mr T. O'Callaghan, P.M., heard evidence from

bank teller Andrew Frewin, who was still suffering from the effects of the pepper attack ; ledgerkeeper John Hayes, who fired the fatal shot ;

Mrs Ethel Halloran, who tried to restrain Dickson ; farm labourer John McKenzie, who lived with Dickson in West Melbourne, and Plainclothes Constable L.M. Coysh,

who accompanied Dickson to hospital and heard his dying words.

Mr O'Callaghan concluded that John Hayes was justified in shooting Dickson, even though his own life was not directly threatened.

Hayes, as the more senior bank officer, had a duty of care to protect his colleague and the property of his employer, the English, Scottish and Australian Bank.

He had acted appropriately and was fully exonerated.4

Notes and References:

Friday 16 February 1900 was Eva Dixon's special day. She was to marry her sweetheart Daniel and their first baby was already on the way.

The bridal couple travelled to Lyndhurst in Rathdowne Street, Carlton, and were welcomed by Rev. Archibald Turnbull.

He was a socialist clergyman, well known for his political activism, and he advertised marriage services at his residence.

The wedding ceremony was conducted according to the rites of Our Father's Church and witnessed by two of Rev. Turnbull's daughters, Ada and Mary.

Vows were exchanged, documents were signed and the marriage was duly registered under the names of Eva Emma Dixon and Daniel Samuels.

But something was wrong. Daniel Samuels was not the man he claimed to be and his past would soon catch up with him.

1,2,3

Daniel Samuel Stroud was born in Sandridge (later Port Melbourne) on 17 March 1868, the son of Daniel Stroud and Annie Higgins.

In June 1881, he was fined 5 shillings in Emerald Hill (later South Melbourne) Court for pledging stolen items of clothing at a pawnbroker's shop.

The pawnbroker, Gottlieb Wielsch, was fined the greater amount of £5 for receiving the goods from a child under the age of fourteen,

and without asking his full name.

Six months later, on Christmas eve, Daniel was committed to the Ballarat Boys Home for a period of two years for stealing a goose.

His parents were living in Emerald Hill at the time and Daniel's Children's Register entry reveals something of his home life:

"The police report that the father is a worthless character, a convicted thief and very poor.

The mother is a drunkard and dying of consumption." Daniel's mother Annie Stroud died in 1881, aged 41 years.4,5,6,7

In April 1889 Daniel Stroud, now an adult, married Margaret McKeogh (McKeough) at the Trinity Church in Port Melbourne.

They had a daughter, Mary Ellen, born in 1890.

The couple separated after a few years and in December 1898 Margaret Stroud sued her husband for maintenance of their daughter.

Margaret was living in Footscray and she was known locally by several different surnames, which she adopted to conceal her identity.

She had a boarder, a man by the name of Stevens who was a convicted criminal, but she maintained that they were not living together as man and wife.

Margaret knew of her husband's living arrangements with his brother and sister-in-law and she expressed concerns that the sister-in-law may not be a fit person to care for the child.

Daniel's defence lawyer, Mr Cunningham, countered Margaret's claims by saying that Margaret herself was not a fit person to care for her own child.

The court decided in favour of the defendant, Daniel Stroud, and dismissed Margaret's maintenance claim.8,9,10

Margaret Stroud died on 6 April 1900, seven weeks after Daniel's marriage to Eva.

Her death notices reads: "STROUD. – On the 6th April at the residence of her sister, Mrs. Stephens, 84 Moreland-street, Footscray, Margaret, the beloved wife of Daniel Stroud,

aged 35 years. R.I.P." Beloved wife indeed! While Margaret breathed her last breath, her husband Daniel was enjoying married life with another woman.

Daniel Samuel Stroud had falsified his name as "Daniel Samuels", and his marital status as a bachelor, when he married Eva at Lyndhurst in February 1900.

He could not deny the evidence and his goose, like the one he stole in 1881, was well and truly cooked.

Daniel Stroud appeared in Carlton Court in October 1900 to answer charges of perjury and bigamy.

He was accompanied by his wife Eva, who carried a baby in her arms, and he was once again represented by Mr Cunningham.

The court heard statements from Rev. Samford of the Trinity Church, Charles George Stephen (Margaret's brother-in-law) who was a witness to the first marriage

and Rev. Archibald Turnbull, who performed the disputed second marriage ceremony.

Eva declined to make a statement, as advised by Mr Cunningham, on the ground that a wife could not give evidence against her husband.

The court agreed that both charges would be heard together and Daniel Stroud was committed for trial in the Criminal Court in early 1901.11,12,13,14,15

In the meantime, Daniel Stroud was granted bail of £20 and, as a widower, he was free to marry.

He lost no time in legitimising his marriage to Eva, and the birth of their son Charles Daniel.

This took place on 16 November 1900, nine months to the day after their first bigamous marriage.

The marriage ceremony was once again conducted by Rev. Archibald Turnbull, but this time at the couple's residence in Spottiswoode (later Spotswood).

The trip from Carlton to Spottiswoode may have been difficult for Rev. Turnbull, as he was not in the best of health at the time and he died four months later in March 1901.

Daniel Stroud had his day in court on 22 February 1901 when, undefended, he pleaded guilty to both charges.

He had an unexpected ally in Crown Prosecutor Mr Finlayson, who cast aspersions on the character of Daniel's first wife Margaret,

claiming she had deserted him and taken up with a disreputable man.

Judge Williams took a lenient view and allowed Daniel Stroud to go free, with a twelve month suspended sentence on his entering into a good behaviour bond and a surety of £25.

Having escaped imprisonment, Daniel, Eva and their baby son Charles could have settled down to a happy family life. But more trouble was just around the corner.

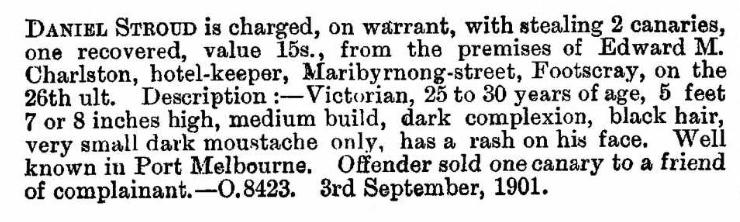

In August 1901 Daniel stole two canaries, valued at 15 shillings, from the premises of hotel-keeper Edward Charlston in Footscray.

He made the mistake of selling one of the canaries to a friend of Mr Charlston.

A warrant was issued for the arrest of Daniel Stroud, but it was never executed because he had disappeared, deserting his wife and baby.16,17,18,19

There was worse to come. Daniel's son Charles died on 16 October 1901, aged 15 months: "Patient little sufferer gone to rest".

A death notice appeared in The Age in November, possibly in the hope that Daniel would return home to share his wife's grief.

When she filed for divorce in 1905,

Eva stated that she believed her husband had deserted because he was afraid of imprisonment if he was found guilty on the larceny charge, and for breaking his good behaviour bond.

There was a gap of four years between Daniel's desertion and Eva filing for divorce.

In the intervening years, she lived with several family members and worked as a domestic.

Eva had several bouts of illness and hospitalisation, when she was unable to work and earn a living, and she gave this as an explanation for the time delay in her divorce petition.

The divorce case was heard in November 1905 and, as expected, Daniel Stroud did not appear to defend himself.

A decree nisi was granted on 17 November 1905 – five years and one day after Daniel and Eva were legally married –

and the decree was made absolute two years later on 6 December 1907.

Eva may have remarried because there was a marriage registered for Eva Emma Dixon (her maiden name) and Frank Henry Nerston in 1907.

20,21,22,23,24,25

What happened to Daniel Stroud? By a strange co-incidence,

a man by the name of Daniel Samuel Stroud enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in 1915.

According to his attestation document, he was born in Melbourne on 17 March 1878 – ten years to the day after the birth of Daniel Samuel Stroud, the convicted bigamist.

Significantly, he answered "no" to the questions "Are you married?" and "Have you ever been sentenced to imprisonment by a civil power?"

The physical description from his medical examination approximates details in the Police Gazette notice

– Height: 5 feet 7 inches ; Complexion: Dark ; Colour of hair: Dark brown.

Could a man who once falsified his name and marital status also be capable of falsifying his date of birth and passing himself off as a much younger man?

Private Daniel Samuel Stroud died of pneumonia, while on active service in World War 1, on 3 July 1916.

He was buried in Bailleul cemetery in France.26,27

Notes and References:

The woman stood in the witness box at the City Court and faced His Worship, Mr Call.

It was Valentine's Day, 14 February 1884, but Mr Call's scathing comments carried no terms of endearment:

"You're not fit to be spoken of as a creature, let alone a woman."

Who was this woman and what had she done to earn this epithet? 1

On a summer evening in December 1883, two young men named Edward Meaker (Maker) and Albert Fox were walking home.

As they approached the Carlton Refuge in Keppel Street, they were astonished to see an infant, wrapped in newspaper,

lying on the footpath the near the doorstep. The Carlton Refuge was a home for "fallen women", not a foundling home, but possibly a mother

in desperate circumstances had left the infant there in the belief that it would be cared for.

The little waif could have died overnight from exposure or lack of nourishment, so Mr Meaker carried him to the nearest police station.

Sergeant Dalton took charge and sent the infant to the "industrial schools", an institution for the care of neglected children.

He was subsequently placed in foster care with Eliza Smith of Sandridge (Port Melbourne).

Enquiries were made and within a few days the infant was identified as Arthur George Wright, the five month old son of Martha Letitia Wright.

2,3

Martha Wright (née Gillon) was an American-born widow from country Victoria, and she had moved to Melbourne following the death of her husband, Philip Wright.

They were married at Christ Church, Castlemaine, in February 1870 and had six children, of whom two (Philip and John) died in infancy.

The youngest child, Phillippa, was born in Prahran in January 1880, seven months after the death of her father.

Philip Wright was an engineer and he worked in the mining districts of Victoria.

He died at Castlemaine on 5 July 1879 at the age of 42 years and, as he left no will, letters of administration were granted to his widow Martha as sole beneficiary.

The estate was valued at £318, 15 shillings and 10 pence, the balance of which was a life insurance policy of £200 with the Mutual Provident Assurance Society.

4,5,6,7

Within weeks of Philip's death, the sale of the household furniture and effects – tables, chairs, couch, carpets,

double and single iron bedsteads, chest drawers, washstands, dressing tables, copper boiler, kitchen utensils, etc. –

was advertised in the Mount Alexander Mail.

Martha, with three young children (Francis, Mary and Ralph) and another on the way, had made the decision to sell up and leave Castlemaine for Melbourne.

In January 1882, Martha became licensee of the Newmarket Hotel in Elizabeth Street, Carlton.

She held the licence for just over a year, when it was transferred to Henry Long in April 1883.

Martha would have been about six months pregnant at the time and she gave birth to another son, Arthur George Wright, in Richmond in July of the same year.

8,9,10,11

On Tuesday 7 December 1883, Martha was arrested at Royal Arcade in the city and charged with having unlawfully abandoned her male child five months old.

At the City Court on the following day, she initially denied that the abandoned child was hers,

claiming she had looked after him for his mother, a woman named Emma (Emily) Harper.

However, she refused to disclose Emma's address and several witnesses testified that Martha had a child about the same age as the one found near the Carlton Refuge.

Besides, the birth of Arthur George Wright had been registered under his mother's married name, with an unknown father.

Martha was remanded to appear in Carlton Court on Wednesday 19 December, where she was committed for trial in the new year.

In the meantime, Martha did not take her son Arthur home and he remained in the care of Eliza Smith.12,13,14,15

Martha was back in court on 4 February 1884, to face charges of abandoning a child under the age of two years,

whereby its life was endangered, and with exposing the child, whereby its health was liable to be permanently injured.

Judge McFarland conceded there was no doubt that Martha had abandoned her child in Carlton,

but he left it to the jury to decide whether her intention was that the child should be discovered and cared for by others.

The fact that the child was found in a public street near the Carlton Refuge supported her case.

The jury was sympathetic to the plight of a poor widowed mother and found her not guilty.

Martha was cleared of the charges, but the future of her son was yet to be decided, and this is how she incurred the wrath of Mr Call.

16

If Martha expected a sympathetic hearing from Mr Call a few days later, she was sorely mistaken.

When questioned, Martha stated that she would lose her employment situation if she had to nurse her child,

and she had not taken out a maintenance order against the father of her child, which would have helped relieve the financial burden.

Mr Call was unimpressed with Martha's demeanour and her lack of interest in her child.

He adjourned the case for another month, in the hope that Martha might develop some maternal feeling for her child.

But when Martha returned to court in March, she was unrepentant and did not want to take her child back.

Mr Call did not hold back on his condemnation of Martha as a heartless mother:17,18

Was Martha really the heartless mother she was made out to be?

Life had dealt her some heavy blows.

She had lost two children in infancy, then her husband in 1879, leaving her a widow with the care of four young children.

A few years later, she found herself pregnant with another man's child.

Could Martha's emotional detachment from this baby be explained as a symptom of postnatal depression, the effects of which are now known to persist for months, even years, after birth?

Martha lived at a time when motherhood was venerated, but women who did not conform to society's ideal were condemned as "bad mothers".

Perhaps history will not judge Martha so harshly.

Notes and References:

A hasty marriage, an unexpected birth and a tragic discovery at the cemetery – all this happened within a few weeks in April and May of 1884.

On the afternoon of 12 May 1884 Joseph Walkerden, a bricklayer, was near the Melbourne General Cemetery when he saw a woman drop something over the fence.

His suspicions aroused, he alerted police and went to the cemetery with Constable Walters to investigate.

They found a cigar box lying on the ground and, on opening the box, discovered the dead body of an infant.

Constable Walters took charge of the body and delivered it to the Melbourne Hospital for a post mortem examination.

Mr Walkerden gave a description of the woman, initially believed to be the infant's mother, to the police.

She was tracked down and arrested, then the truth – or at least part of the truth – came out.

Catherine Howard, aged 43 years, was not the mother of the infant, but a nurse who had attended the birth.

She claimed the infant was stillborn and she admitted having disposed of the body in the cigar box "to oblige another woman".

Nurse Howard was remanded in Carlton Court for seven days while police continued their investigations.

They had to establish whether there were any suspicious circumstances surrounding the infant's death.1

The inquest was held at the Melbourne Hospital on Thursday 14 May. Susan Copeland, the woman identified as the mother,

stated that she had given birth to a stillborn female infant on 11 May and was attended by the nurse Catherine Howard.

A doctor was not called in to certify the stillbirth.

Susan Copeland had given Catherine Howard the sum of £1 to arrange burial of the child, with the proviso that she could return for more money if required.

As the nurse did not return, Mrs Copeland assumed that the burial had been completed as per her wishes,

and she only found out about the body in the cigar box when she read it in the newspaper.

The doctor who conducted the post mortem examination found that the infant was born prematurely at about six or seven months' gestation.

There were no marks of violence or any evidence of injury on the body.

He could not say definitely whether or not the infant had breathed, but he believed that she would not have lived.

The coroner, Dr Youl, found that the infant was stillborn and the jury returned the same verdict.

According to this finding, neither Susan Copeland nor Catherine Howard was in any way implicated in the death of the infant,

and there was no charge of infanticide or murder to answer.2

However, Catherine Howard's actions in accepting the payment, then failing to give the child a proper burial, were both dishonest and dishonourable.

A week later, on 21 May, she appeared in Carlton Court to face a charge of concealment of birth, an offence under the Crimes Act.

This was a lesser charge than the capital crimes of infanticide or murder, but it still carried a prison sentence.

Fortunately for Catherine, the case was dismissed in a matter of minutes.

The Bench, comprising Messrs Conroy and Showers, took a merciful view, and considered that she had erred through ignorance and not through criminal intent.

Co-incidentally, the hearing was scheduled on the same day that Susan Copeland sought a maintenance order against her husband, Nathaniel Copeland.

Newspapers at the time did not report whether there was any interaction between the two women at the court but, given their recent history, it was unlikely to be cordial.

3

The maintenance case revealed the extraordinary circumstances of the marriage of Susan Reed, as she called herself, to Nathaniel Copeland.

They had married in Carlton on 28 April 1884, after a whirlwind courtship of only a few weeks.

Nathaniel Copeland, a dealer, had met Susan by chance at the Swan Hotel in Fitzroy.

Irish-born Susan was an attractive woman in her twenties and Nathaniel admitted he was "struck" by her.

Susan told Nathaniel that she was a widow, her husband having died three years previously in Adelaide.

She was in receipt of an income of £1 per week and was entitled to a legacy.

The marriage was registered by John Glennon of Drummond Street, Deputy-Registrar for Carlton, and William Fogg, a cabdriver, was present as a witness.

Within two weeks of the marriage, Susan Copeland gave birth to the stillborn infant that Catherine Howard threw over the fence into the cemetery.

Did Nathaniel Copeland even know that his new wife was pregnant at the time of their marriage?

Had she tried to trick him into accepting another man's child as his own?

Whatever his reasons, Nathaniel had allegedly kicked Susan out of the house and left her destitute.4

Nathaniel claimed that he had given Susan money amounting to £45, two thirds of which she had spent buying stock for a shop.

He was unemployed at the time of the maintenance case and surviving on an income of about ten shillings and sixpence a week.

He considered that his wife's independent income of £1 per week – almost twice his current income –

should be adequate to cover her living expenses. The Bench made a maintenance order for five shillings a week, with 26 shillings costs.

The honeymoon was well and truly over and Nathaniel Copeland must have rued the day he first caught sight of Susan Reed in the Swan Hotel.

Nathaniel and Susan Copeland continued to live apart and in December 1885, at Nathaniel's instigation,

a formal deed of separation was drawn up by solicitor James McKean and signed by both parties.

This document set off a chain of events that ultimately saw Susan Copeland imprisoned on a charge of bigamy.5

In April 1886, two years after her marriage to Nathaniel Copeland, Susan made the acquaintance of Daniel Moroney (Maroney).

In a repeat performance of her courtship with Nathaniel Susan, now using the name "Alice Rehde",

told Daniel that she was a widow and her husband had died four years previously.

Daniel, an older man, had taken over the licence of the King's Arms Hotel in Lygon Street in April 1885

and he probably thought that an attractive young wife at his side would be a boon to business.

They were married on 10 May 1886, and this time they had a church wedding at St Georges chapel in Drummond Street, Carlton.

The ceremony was conducted by the Rev James O'Connell, in the presence of Daniel Carrol and Kate Murray as witnesses.

The newly married couple had six weeks of wedded bliss before Susan's duplicity was exposed.

She was arrested at the King's Arms Hotel on 23 June 1886 and appeared in Carlton Court a week later to answer a charge of bigamy.

Susan was committed for trial at the Supreme Court and granted bail of £100.6,7,8

The bigamy case was widely reported in local and interstate newspapers.

As often happens when the defendant is a woman, the reporting commented on Susan's physical appearance.

She was variously described as "a very pleasant-featured woman, well dressed, and of very respectable appearance"

and either "25 years old" or "35 years old" or "middle-aged".

None of these age descriptions tallied with Susan's birth year of 1858, as stated in her prison record. Did Susan lie about her age as well as her name and marital status?

The sometimes tearful woman was not represented in court and her primary defence was the wording of the separation agreement,

and her belief that the document constituted a legal divorce and rendered both parties free of any future obligation to each other.9,10,11,12

"The said Susan Copeland shall henceforth, during the life of the said Nathaniel Copeland, live separate and apart from him as if she were sole and unmarried,

and shall be free and discharged from the power, control, restraint, authority, and government of the said Nathaniel Copeland,

and he will not and shall not in any way personally or by procurement annoy or molest her,

or in any way interfere with her as to the place or places where she may live or reside, or her manner of living,

or with any person or persons with whom she may reside, nor require, or by any proceedings of nature,

attempt or compel her to return to cohabitation with him, but that she shall have full liberty to go where,

and reside with such person or persons as she may from time to time think proper."13

Mr Justice Higinbotham of the Supreme Court accepted that the agreement may have misled Susan into thinking she was free to marry,

but she had failed to disclose to Daniel Moroney that she had married Nathaniel Copeland in 1884.

She had also deceived Moroney by using the name "Alice Rehde", instead of her legally married name of "Susan Copeland".

Justice Higinbotham considered that Susan's plea of ignorance was no valid defence and, after a short deliberation, the jury found her guilty of bigamy.

James McKean, the solicitor who had drawn up the separation agreement, appeared at the sentencing hearing two days later on 30 July.

He explained his absence from the court on a previous occasion by stating that he had been engaged in another case at Collingwood Court on the same day.

Mr McKean gave the rather lame excuse that he thought his client had fully understood the terms of the agreement but, in hindsight,

he should have explained that the agreement did not constitute a legal divorce, nor was he in a position to grant a divorce.

Justice Higinbotham thanked Mr McKean for his explanation and sentenced Susan Copeland to three months' imprisonment.

According to the Victoria Police Gazette, she was released from prison in the week ending 18 October 1886.14,15

After her sensational bigamy trial and subsequent imprisonment, Susan Copeland seemed to disappear from public view.

She may have changed her name or possibly found another gullible man to marry.

Nathaniel Copeland died in July 1907.

Daniel Moroney held the licence of the King's Arms Hotel until September 1886, when it was transferred to William Edwards, and Moroney was declared insolvent.

The hotel was later renamed the Horseshoe Hotel and it was delicensed in December 1925.

Joseph Walkerden, the man who alerted police to the grim discovery in Melbourne General Cemetery in May 1884,

committed suicide at his home in Reeves Street, Carlton, in November 1898.17,18,19

Notes and References:

In 1915, John Moran was one of many young Australian soldiers who died, but his name was not honoured amongst the fallen.

He did not die a heroic death on the battlefield, or in a military hospital from injury or disease.

Instead, he died trying to escape from a thwarted burglary attempt at the North Carlton Drill Hall in McIlwraith Street.

John Moran did not give his life for his country, he gave it for a few pounds in cash and cheques.

On the morning of 17 February 1915, Richard Rockett was making preparations for the day's work.

He was a carrier living in Wilson Street, Princes Hill, and he kept his horses in a vacant paddock next to the North Carlton railway station.

Having collected the horses, he walked back along Wilson Street and, shortly after 6.00 am, he noticed a man in a soldier's uniform lying face downwards on the ground opposite the drill hall.

He thought the man was asleep – possibly sleeping off the effects of a night's drinking – and went to wake him.

The man was unresponsive but, because his body was still warm, Rockett hastened to fetch Dr Howard, who lived nearby.

It was too late, all Dr Howard could do was certify the death.

The police were called in and they were soon able to connect the deceased man with events of two hours before at the drill hall.

The man had been shot by Sergeant Major Charles Kerry at about 4.30 am and he had slowly bled to death from a bullet wound in the back.1,2

The shooting of a soldier by an army officer on Australian soil was sensational news, with headlines proclaiming: "Soldier-burglar shot dead" and "Sergeant Major's deadly aim".

The soldier was identified as nineteen year old John Patrick Moran, a member of the Expeditionary Force.

His father, Nicholas Moran, faced the grim task of formally identifying the body at the city morgue.

Mr Moran, having lost his wife Mary Ann in 1895, had been dealt another blow.

When John was born in Port Melbourne in 1895, the birth was not the happy event that his family may have wished for.

His mother Mary Ann Moran (née Stafford), developed septicaemia after giving birth and died on 29 September, when John was just 15 days old.

He was baptised on the same day that his mother died, and she was buried two days later in Melbourne General Cemetery.

John and his brother James, who was 2 years older, may have spent some time in care, as they had a foster mother, Mrs Kathleen Kelly,

living in Trinity Street, Brunswick.

When World War 1 was declared, John was one of the earliest enlistments (no. 134) on 17 August 1914.

He gave his trade or calling as "engineer" and nominated his brother James as next of kin.

John was single at the time of his enlistment, but a few weeks later he married Rose Ellen Strattan at the Church of England, Glenlyon Road, Brunswick on 9 September 1914.

As his wife, Rose was allocated ⅖ ths of John's army pay.3,4,5,6,7

John Moran was assigned to the 7th Battalion, which was raised by Lieutenant Colonel H.E. "Pompey" Elliott within a fortnight of the declaration of war.

On Wednesday 19 August 1914, John joined thousands of volunteers marching the twelve miles from Victoria barracks in St Kilda Road to Broadmeadows, then a farming area northwest of Melbourne.

The streets were lined with cheering crowds and newspaper reports commented on the camaraderie amongst the volunteers and the egalitarian nature of the march,

where "bank clerk and bricklayer, public school man and navvy, will be swallowed up in the universal khaki."

After leaving the city proper, the volunteers headed north towards Sydney Road, where they stopped near Carlton Oval in Princes Park for lunch,

finally arriving at the Broadmeadows Camp in the late afternoon.

Accommodation in the hastily erected camp was basic, with no permanent huts, and soldiers had to sleep in crowded tents, often in cold, wet and muddy conditions.

John Moran had five years' experience as a school cadet, and many of his fellow recruits would have had some form of compulsory military training between the ages of fourteen and eighteen years.

They settled into an intensive training routine of physical drill, squad drill, rifle exercises and lectures.8,9,10,11

After two months of preparation for war, the 7th Battalion embarked for Egypt, via Albany in Western Australia.

The soldiers boarded a train at Broadmeadows station early on Sunday 18 October and headed for Port Melbourne,

where they marched down the pier to HMAT Hororata. They were joined by the 6th Battalion and the ship left Port Phillip Bay the following morning.

But where was John Moran? His name does not appear on the embarkation roll and his father later thought that a motor car accident could account for his not being on active service.

However, there is nothing in his service record to indicate any such accident or his being medically unfit for duty.

Nor is there any indication of misconduct or absence without leave.

John Moran's service record is notable for its lack of information – he seems to have disappeared without anyone in authority noticing.

Had the rush of excitement he felt on enlistment given way to the harsh reality of training for war?

An annotation, added after his death, simply states: "Deserted for a considerable period prior to being killed" and the circumstances of his death are recorded by a newspaper clipping.

The last family member to see John alive was his father, Nicholas Moran.

According to Mr Moran's inquest statement, John had visited him at Port Melbourne on 6 February.

He mentioned a motor car accident and, as he was short of money, Mr Moran lent him £1.12,13,14

The North Carlton drill hall, located in McIlwraith Street north of Pigdon Street, was opened in January 1915.

Within the first month two burglaries had taken place, on 31st January and on or about 7 February.

The timing of the second burglary a day or two after John Moran's visit to his father was no coincidence.

He was, by his own admission, short of money and may have seen the drill hall as an easy target.

When Moran's clothing was searched, he was found in possession of multiple sets of keys, some of which fitted locks at the drill hall and the North Carlton bowling club,

and two cheques stolen previously from the drill hall.

After the second burglary the Commanding Officer gave orders for the drill hall to be watched overnight.

As well as items of monetary value – cash, cheques and railway travel vouchers – important military documents were stored there.

Australia was at war and if these documents fell into the wrong hands the consequences could be disastrous.15,16

On the evening of 16 February, the two officers allocated for night watch did not turn up for duty,

so Warrant Officer John Francis Brady arranged for Sergeant Major Charles Kerry to stay overnight.

He was issued with a rifle and ammunition and his instructions were to apprehend any intruder and notify Detective Mercer of Victoria Police.

Charles Kerry was asleep on a camp bed when he was woken by a noise at about 4.30 am.

He saw a light switched on in the Commanding Officer's room and went to investigate, then the light was suddenly switched off.

An intruder was on the premises and he or she had to be stopped.

Kerry called out "Hands up", and in the darkness he saw a figure running towards the main entrance.

He fired a shot, but the intruder kept running and exited the building, slamming the main door behind them.

Charles Kerry had to make a split second decision. Should he go after the intruder or return to his post and secure the premises?

He chose the latter and John Moran's fate was sealed.

Kerry telephoned the North Carlton police, who arrived at 4.45 am and made a search of the premises and surrounding area.

They found nothing amiss, so Sergeant Major Kerry finished his shift at 5.00 am and went home, not knowing that he had shot a man who lay dead or dying less than 100 yards from the drill hall.17

What were John Moran's final thoughts as he lapsed into unconsciousness from loss of blood?

Did he think of his family – his wife Ellen, his father Nicholas, his foster mother Kathleen and his brother James – or of the folly of committing a petty crime that would end his life?

Had circumstances been different, his life may have been saved with prompt medical assistance.

If the two allocated officers had turned up for duty on the night, one could have gone after the intruder while the other secured the premises.

If the police had been more thorough in their search, John Moran's body may have been found earlier.

But there was a practical limit to the search area the police could cover in the dark hour before dawn.

Had John Moran's life had been saved, he would have faced a court martial and, most likely, a custodial sentence in a civilian prison.

Instead, he was laid to rest in an unmarked grave at Fawkner Cemetery the next day on 18 February 1915.18

The inquest was held a week later on 25 February and reporting of the verdict was as sensational as that of the shooting incident.

The Coroner, Dr R.H. Cole, heard evidence from Dr Mollison, who performed the post mortem examination, Sergeant Major Charles Kerry,

Warrant Officer John Francis Brady, Nicholas Moran, Ellen Moran, Richard Rockett, Detective Mercer and the police officers who attended the scene.

No other representative from the armed forces was called to give evidence.

Dr Mollison described, in clinical detail, the "small rounded penetrating wound … to the right of the midline" and gave the cause of death as haemorrhage from a gunshot wound in the lower back.

Warrant Officer Brady recounted the events of the night before the shooting, his instructions to apprehend the offender and

that he had issued Sergeant Major Kerry with a rifle and ammunition because the offender could be armed.

It was then Charles Kerry's turn to give evidence.

He stated that, upon hearing the disturbance, he had taken the loaded rifle "with the object of capturing the intruder"

and he had fired at the retreating figure "in order to bring him to a stand."

The Coroner found "… that John Moran died from a gunshot wound in the body …

and the said wound was inflicted by Sergeant Major Kerry in the execution of his duty and advancement of law."

The shooting of John Moran was justified and Sergeant Major Charles Kerry was fully exonerated. 19

Two months after the inquest, on 25 April 1915, John Moran's fellow soldiers of the 7th Battalion landed at Gallipoli and an Australian legend was born.

John's brother James Joseph Moran enlisted soon afterwards on 21 June 1915.

He was assigned to the 21st Battalion and, like his brother, he trained at Broadmeadows Camp.

James saw active service in Europe and he was awarded the military medal for bravery in the field in 1918.

He returned to civilian life and lived in Brunswick, while his father Nicholas Moran remained in Port Melbourne.

Nicholas died in June 1935 and James in August 1970.

Both father and son are buried with Mary Ann in Melbourne General Cemetery, near the north gate and only a few blocks away from the drill hall where John breathed his last breath.

James Michael Stafford, possibly a relative from Mary Ann's family, was buried with John Moran at Fawkner in 1973.20,21,22,23

The North Carlton drill hall served its purpose during the war years and was relocated elsewhere on the site after World War 1.

Part of the former council land bounded by Pigdon, McIlwraith, Wilson and Holtom Streets was released for educational purposes in December 1920.

The school that later became known as Princes Hill Primary School was built there and opened on 16 April 1924.

The land north of the school was retained for use by the army during World War 2, and the army reserve through to the 1990s, when the drill hall was permanently removed.

The vacant land was enclosed in a cyclone wire fence while the Commonwealth Defence Department considered its disposal.

It was prime real estate land, close to parks and schools, and could fetch a high commercial price.

However, local residents and school groups favoured the land being made available for community and school use.

Another proposal to build a sports stadium on the site was rejected.

Both proposals would have required a considerable financial contribution from the Victorian Government. In the end, money won out.

The land was released for residential development in 1998 and townhouses were built on the site.24,25,26,27,28,29

Related Item: Carlton in the War

Notes and References:

September 2019 marks the 85th anniversary of one of the most sensational cases in 20th century Australian criminal history.

The story of the so-called "Pyjama Girl" has been told many times over – in newspapers, books, television, film and on stage –

and the romantic notion of a young woman in silk pyjamas has, to some extent, overtaken the harsh reality of her brutal death.

Her public story began on the morning of 1 September 1934, when a woman's partly burnt body was found stuffed into a culvert on the Howlong Road,

near Albury in New South Wales.

Her body was dressed in the tattered remains of oriental-style pyjamas, hence the name "Pyjama Girl".

She had suffered extensive head injuries, from multiple blows, and a post-mortem examination revealed a bullet wound in her neck.

New South Wales police faced the daunting task of identifying the woman, who could be any one of a number of missing women on record at the time.

The Pyjama Girl body's was embalmed and transferred to Sydney University, where she lay, preserved in formalin, in a zinc-lined coffin for nearly ten years.

Her face was made up to appear more lifelike and she was viewed by hundreds of people –

family, friends and workmates of missing women and even the man later charged with her murder – but no conclusive identification was made.

A major breakthrough came in March 1944, when the New South Wales Commissioner of Police, William John MacKay,

elicited a confession from an Italian man named Antonio Agostini.

At the time of his confession, Antonio was a recently-released World War 2 internee and he was working at the well-known Romano's restaurant in Sydney.

Ten years earlier, in 1934, he was living with his wife Linda above a shop in Swanston Street, Carlton.

He stated that Linda had pointed a gun at him and she had been accidentally shot when he tried to disarm her.

Antonio had waited until nightfall then he loaded Linda's body, wrapped in a towel and sacking, into his car and drove through the night to New South Wales.

He dumped the body in the culvert, doused it with petrol and set fire to it in order to prevent identification.

(His mistake was not knowing that the human body has a high water content and is not easily burnt.)

Antonio Agostini was charged with murder and, as the crime had been committed in Victoria, he was extradited to Melbourne to face trial.

This placed the death scene in an upstairs bedroom of 589 Swanston Street, Carlton, the business address of the Italian newspaper Il Giornale Italiano,

where Antonio worked as a journalist and agent for the newspaper.

The Pyjama Girl's body was transferred to the Melbourne City Morgue, where she was kept under guard as crucial evidence in the murder investigation.

She was subjected to another post-mortem examination and inquest, held over multiple sittings from 23 March to 2 May 1944.

The purpose of the second inquest was threefold: To establish the identity of the Pyjama Girl, to determine the cause of her death and who (if anyone) was responsible for her death.

Whoever she may have been in life, the Pyjama Girl's body was laid bare in death.

The physical evidence of her dental fillings, the colour of her eyes (blue, brown or hazel?), the shape of her hands and ears,

and even the size and shape of her breasts was presented in clinical detail.

One witness, Mrs Jeanette Routledge from Bomaderry, New South Wales, was convinced that the Pyjama Girl was her daughter, Anna Philomena Morgan, who she last saw in 1930.

Her claim was supported by Dr Palmer Benbow,

who presented evidence based on a detailed photographic comparison of facial features of both women.

Mrs Routledge proved to be an unreliable witness and, under questioning, she admitted that she had given false information to police in order to avoid implicating herself in her daughter's disappearance.

At the conclusion of the inquest the coroner, Mr Tingate, identified beyond reasonable doubt that the Pyjama Girl was Linda Agostini

and that she had been killed by her husband Antonio Agostini.

He committed Antonio Agostini for trial on a charge of murder.

The murder trial took place before Justice Lowe in the Supreme Court of Victoria, commencing 19 June 1944, and Antonio pleaded not guilty to the murder of his wife.

The private lives of Antonio Agostini and Linda Platt were made open to public scrutiny.

Italian-born Antonio and English-born Linda were married in Sydney in 1930.

They were an attractive couple and Linda, who had worked as a hairdresser, was always well groomed.

But, according to Antonio, Linda had a dark side, particularly when she drank to excess, and she had left him for months at a time.

Early one morning, on or about 27 August 1934, Antonio woke to find Linda pointing a gun at his head and she was accidentally shot during the ensuing struggle.

Antonio later threw the weapon in the Yarra River and the only remaining physical evidence of the shooting was the bullet extracted from Linda's neck.

However, according to the post-mortem report, the bullet wound was not the cause of death.

Instead, the multiple injuries on the left side of her head saw Linda's demise.

Antonio explained the head injuries by stating that he had accidentally dropped Linda's body while he was carrying her down the stairs

and that she had hit her head on a heavy object at the bottom of the staircase.

If Antonio's statement was true and correct, it is a chilling thought that Linda may have still been alive when he dropped her body on the stairs.

Could the accidental shooting and the accidental dropping of the body on the stairs be too much of a coincidence?

This was crucial in deciding Antonio's fate.

If the bullet wound had caused Linda's death, Antonio could plead self defence, which could, in turn, lead to an acquittal.

However, the inquest had established that the head injuries, so severe that part of Linda's skull had caved in and exposed her brain, were the cause of death.

The injuries were consistent with multiple blows, rather than a single impact with a hard object, suggesting an intentional act of violence resulting in death.

The text of Antonio's confession is reproduced verbatim in Richard Evans' book The Pyjama Girl Mystery,

and nowhere in this carefully worded and detailed account of Antonio's actions does he mention dropping the body on the stairs.

This omission, and other inconsistencies in Antonio's stated evidence, pointed to a murder conviction and possible death sentence.

But there were also alleged procedural irregularities by New South Wales police in obtaining Antonio's confession

and suggestions of a deal being done in order to close the long-running case.

If these allegations were proven, the case could have been thrown out of court.

The jury had much to consider when they retired on 28 June 1944.

Was Linda Agostini the victim of an accidental death or of extreme domestic violence?

After nearly 2 hours' deliberation the jury found Antonio Agostini not guilty of murder, but guilty of manslaughter.

Two days later, on 30 June 1944, Justice Lowe sentenced Antonio Agostini to six years imprisonment, with hard labour, to be served at Pentridge Prison in Coburg.

This was not the first time Antonio had been in detention since his arrival in Australia in 1927, though the circumstances were very different.

Just before the outbreak of World War 2 in August 1939, he came to the attention of the Commonwealth Investigation Branch for his former membership of the Fascist Party and his self-description as "a Fascist at heart".

His dossier included the statement "Married: Wife deserted five years ago. Her whereabouts are not known."

Antonio was living the lie of his wife's disappearance.

His name appeared on a security list of Italians recommended for internment in the event of hostilities with Italy.

He was "captured" at Darlinghurst, Sydney, in June 1940 and interned as an enemy alien.

During his internment, Antonio made an unsuccessful application to be repatriated to Italy, in a reciprocal exchange with British journalists stranded by war in that country.

Antonio Agostini was finally released from internment in February 1944, when he was deemed medically unfit for the Civil Aliens Corps, and transferred from the Wayville internment camp to Sydney.

A month later, in March 1944, the nightmare of the Pyjama Girl case had begun.

Antonio served four years of his six year manslaughter sentence, with remissions for good behaviour and as part of a general post-war amnesty for former internees.

While technically a free man, he faced a deportation order on his release from prison.

He was detained in Pentridge until the next available ship bound for Italy was due to depart from Port Melbourne.

Antonio's departure was not without drama. His transfer from Pentridge to the ship Strathnaver took place in the early hours of the morning on 22 August 1948.

Immigration officials were anxious to avoid a "media scrum", but some news reporters managed to photograph and communicate with Antonio on board.

Antonio was closely guarded until the ship left Port Melbourne on the next day, 23 August 1948 and, once at sea, he was free to move about the ship and mingle with other passengers.

He returned to his homeland of Italy but, with memories of his wife Linda and his incarceration in Australia, would he ever be free?

Antonio married Giuseppina Gasoni, a widow, at Cagliari, Sardinia, in December 1952.

On 7 September 1959, the Truth newspaper reported that Antonio was making enquiries about returning to Australia, but nothing came of these claims.

Antonio Agostini died ten years later, in 1969, and was buried in San Michele cemetery.

Linda Agostini was laid to rest at Preston Cemetery on 13 July 1944.

She had no family in Australia and, to save her the final indignity of a pauper's grave, the Victorian government paid for her funeral and burial.

Her grave is marked by a simple wooden cross, bearing the name "Linda Agostini" and her years of birth and death in faded letters.

But, to this day, a lingering doubt about the true identity of the Pyjama Girl still remains.