Travelling In Carlton

Carlton has seen many different modes of travel during its history. What was it like travelling in Carlton in the early days? Horse (or goat or donkey) drawn carts, cabs and omnibuses, cable trams, steam trains, "boneshaker" cycles and, when no other means was available, "shank's pony" or walking. Over the years, horse drawn vehicles have given way to motor cars, trucks, taxis and ride sharing services. Cable tram routes have been electrified or replaced by motor bus services, and the former North Carlton railway station is now a neighbourhood house, hosting a range of classes and community activities. Cycling is as popular as ever, facilitated by bike paths along major roads, and walking to work is now considered a lifestyle choice rather than an economic necessity. Here we take a look at travelling in Carlton and how it has changed with inner city growth and development.

Hot Air Ballooning

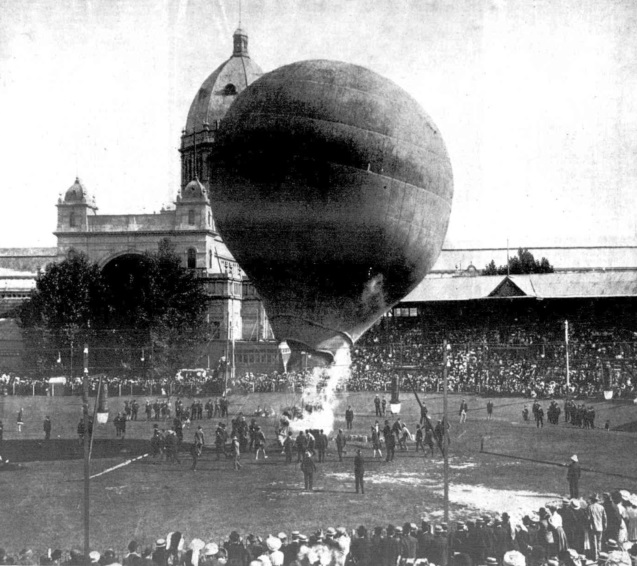

Image Source: Punch, 20 February 1908

Alphonse Stewart's Hot Air Balloon Ascending from the Exhibition Oval in February 1908

Hot air balloons are a familiar early morning sight in Carlton, harking back to a more romantic era in air transport. The first ever balloon ascent in the Australian colonies took place at Cremorne gardens, Richmond, on 1 February 1858. The spectacle was bankrolled by theatre entrepeneur George Coppin, who imported a balloon from England and engaged the services of two aeronauts, Messrs. Brown and Dean. After some delay and a top-up of gas, the balloon ascended, with Mr. Dean on board as the more experienced aeronaut. Dean had a pleasant trip of about 25 minutes and landed safely in the vicinity of Plenty Road, seven to eight miles from Melbourne. George Coppin had offered a reward of £5 to the conveyance that brought the balloon back to the gardens, so there was no shortage of helpers on the ground to load and transport the deflated contraption.1

Mr Brown had his chance to go aloft two weeks later, on 15 February, and his experience was very different. The balloon departed from Cremorne gardens, as before, and ascended rapidly and hovered overhead. Because of the late hour, Brown avoided heading out over the bay, but his choice of going in the opposite direction over the Collingwood Flat proved to be his downfall. He made a gentle descent on the road between the Collingwood Stockade and Brunswick, about four miles from Cremorne, which would have placed him in the area later known as North Carlton or Princes Hill. The party that greeted him was far from welcoming. In his own words:

"On my descent, I was treated in a most brutal manner by the people assembled. Why, I know not ; but they tore the hair from my head, bruised, crushed, and almost suffocated me besides damaging the balloon by tugging at, and trampling on it. This does not apply to Mr. Hugh Peck, of Collingwood, to whom I am under the obligation of returning the balloon to Cremorne in safety, and declining to receive any remuneration for his trouble. Mr. Needham, of the Gasworks, assisted in extricating me from the savages." 2

Who were these "savages"? In 1858, the area north of Reilly (now Princes) Street was virgin bushland and largely uninhabited, apart from the stockade reserve. Mr Brown's tormenters must have come from neighbouring suburbs or followed the progress of the balloon from Richmond. The novelty of the balloon flight may have induced them to take souvenirs, or possibly they were keen to claim George Coppin's reward of £5 for return of the balloon.

Fifty years later, in February 1908, thousands of spectators paid sixpence apiece to watch aeronaut Alphonse Stewart execute a daring triple parachute descent from a hot air balloon. This was not the first parachute descent seen in Melbourne - several years previously another aeronaut had descended in a single drop - but it was the first involving a series of three parachutes, each of which was cut away as the next one opened. The 28 year old French Canadian, dashingly dressed in "a bright blue suit of tights", took off from the Exhibition Oval in the Carlton Gardens and waved to the cheering crowd as the balloon rapidly ascended to several thousand feet. The crowd watched with excitement and tredipation as the aeronaut appeared to drop from the sky, before each of the three parachutes opened and carried him back down to earth.3

In his first descent on 15 February 1908, Stewart narrowly missed telegraph wires and landed safely in Station Street, Carlton. His second descent on 19 February took him further, landing in Lygon Street, North Carlton. Stewart was cheered on by the crowd, but not everyone was happy with the outcome. Collingwood butcher Hughie Hart had his cart commandeered to carry the aeronaut and his parachute, causing considerable damage to the vehicle. The abandoned hot air balloon landed on Mr Dainty's house at 179 Pigdon Street and, as reported by the North Suburban Chronicle, "luckily no one happened to be very near at the time". Stewart's third and final descent on 22 February almost saw his demise. The daring aeronaut landed in the Melbourne General Cemetery, breaking his right leg and putting him out of action for some time. While Alphonse Stewart had suffered many cuts and bruises in over 500 descents during his 10 year aeronautic career, this was the first time he actually sustained a broken bone - ironically in the last ten feet of a 3,000 feet descent. Following his recovery, Stewart was seen walking with a limp and it was later reported that his broken leg had healed two inches shorter as a result of the injury. 4,5,6,7,8,9

By 1913, Carlton was largely built up and this created additional hazards for balloon landings. Austrian aeronaut Zahn Rinaldo had a lucky escape when he crashed through the window of a house in Faraday Street, Carlton. The ascent took place from the Carlton Gardens on Saturday 8 February and was delayed because of problems with inflating the balloon. It was realised, too late, that there was a small tear in the canopy and this grew larger as the balloon ascended and more hot air escaped. The balloon reached an elevation of 200 feet and managed to clear light and telegraph poles, but it was obvious to the spectators on the ground that something was seriously wrong. In the meantime, Miss Barwell, who lived at Miss Dolan's house at 56 Faraday Street, heard the noise of the crowd and went upstairs to get a better view. Imagine her shock when the aeronaut, still attached to the balloon, crashed through a bedroom window.10

Rinaldo, unable to deploy his parachute safely at a low elevation, had attempted an emergency descent in Faraday Street. A sudden gust of wind blew him into the upstairs window, smashing the glass and the timber framework, then the pressure of the balloon swung him out again. In trying to free himself from the trapeze, the small platform on which he stood, he fell to the pavement below, a drop of about 19 feet. Rinaldo was taken, in a state of shock, to St Vincents Hospital, where he had an operation for a dislocated wrist. He also suffered a broken nose and cuts and abrasions from the window glass. All in all, the injuries were relatively minor, considering the circumstances of the crash. Three years previously to the day, on 8 February 1910, Rinaldo collided with a tombstone while making a descent in Melboure General Cemetery. Unlike fellow aeronaut Alphonse Stewart, who broke his leg in the Cemetery in 1908, he was able to walk away from the crash scene.11,12

Miss Barwell was interviewed after the accident and gave her account in The Argus, but the The Beverley Times reported, decades later in 1957, that she had passed out from shock and nobody noticed because all the attention was on getting the injured Rinaldo to hospital. After its release, the rapidly deflating balloon was blown over the roof of the house and damaged the chimney of the neighbouring property. The Argus reported that the balloon came to rest "partly into Murchison square and into the City Council's store-yard". However, this account does not stand up to fact checking. According to maps and directories of the time, the corporation yard was on the corner of Canning Street and Macarthur Place, north of Faraday Street and in the opposite direction to Murchison Square.13,14

The following year, 1914, the world changed irrevocably. Rinaldo was in New Zealand when World War 1 broke out and he was interned on Somes Island, Wellington, as an enemy alien. This was one of two internment camps in New Zealand - the other was at Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf - and it had a bad reputation for poor quality rations and mistreatment of inmates. Answering the call of war, men from Australia and New Zealand enlisted and travelled overseas to fight for the mother country. Hot air balloons were used for observation purposes during military operations and it was dangerous work, as a large balloon hovering overhead would have been an obvious target for enemy fire. By the end of the war, the golden age of hot air ballooning was over. The newfangled flying machines had proved their worth and enabled pilots to perform daredevil stunts at speeds and directions unattainable by air-powered balloons.15,16

In the geopolitical aftermath of World War 1, national boundaries in Europe were redrawn and Rinaldo's birthplace of Cheb in Bohemia became part of the new Czechoslovak Republic. Rinaldo was deemed a Czech national and he had a new passport issued, in his full name of Joseph Anton Zahn Rinaldo, in February 1920. The one-time aeronaut and now "theatrical artist" travelled to Australia via Wellington, New Zealand, on the s.s. Paloona, and arrived in Melbourne on 4 August 1921. As a Czech national, he was required to register as an alien and notify the local police of any change of abode. His application form, signed and dated 4 August 1921, gave his intended place of abode as 278 Faraday Street, Carlton, which was part of Royal Terrace and several blocks away from his 1913 crash scene. He also lived at 246 Drummond Street, Carlton and used the address 123 Canning Street, Carlton, in a copyright application for the dramatic work "A day in dog town or are u going to the dogs" in August 1922. This address was the home of variety artists Francis and Freda Cuthbert. Rinaldo and Freda had a daughter, Cleo, born in about 1924. Cleo followed her parents' career path of vaudeville and circus performing and in 1953 she married into the Bullens' Circus family. Cleo died in 2007. 17,18,19,20

Rinaldo spent the interwar years travelling and working in vaudeville and, from time to time, newspapers revived stories of his hot air ballooning escapades. When World War 2 broke out, Rinaldo was in Queensland and his nationality - originally Austrian and now Czech - was once again at issue. Rinaldo was the first person prosecuted in Ipswich Police Court, in March 1940, for failing to register as an enemy alien. He professed ignorance of new regulations under National Security Act of 1939, believing that he was still somehow covered by his World War 1 registration in New Zealand and his alien registration of 1921 in Melbourne. Rinaldo pleaded guilty and was fined £12/10/, with 6/ costs of Court, and £2/2/ professional costs, in default three months' imprisonment. He was lucky to escape the maximum fine of £100, in default six months' imprisonment, but he could ill afford the lesser amount imposed. His earnings from vaudeville performances had dropped off and he was supplementing his income by working as a tattoo artist and selling fruit to soldiers outside the Redbank military camp. Given this location, he could be considered an "enemy alien" hiding in plain sight.21,22,23

After World War 2, all was forgiven and Rinaldo was naturalised on 15 May 1947. He remained in Redbank, Queensland, and continued working as a tattoo artist. Rinaldo, the man who survived many daredevil stunts, died in Queensland on 2 April 1964, at the ripe old age of 81 years. He was buried in Ipswich Cemetery and went to his grave minus the first joint of his left thumb, a possible legacy of his risky aeronaut career. The missing thumb joint was noted in his alien registration of 1921, which required a fingerprint of the left thumb for identification purposes.24,25,26,27

Notes and References:

1 The Argus, 2 February 1858, p. 5

2 The Argus, 16 February 1858, p. 5

3 The Argus, 17 February 1908, p. 4

4 ibid

5 The Argus, 20 February 1908, p. 5

6 The Argus, 21 February 1908, p. 3

7 North Suburban Chronicle, 22 February 1908

8 The Argus, 24 February 1908, p. 4

9 The Age, 10 February 1910, p. 10

10 Rinaldo's accident was widely reported in newspapers at the time. The Weekly Times of 13 February 1913 included a photo of the smashed window at 56 Faraday Street on page 36.

11 The Argus, 10 February 1910, p. 9

12 The Argus, 10 February 1910, p. 13

13 The Beverley Times, 15 August 1957, p. 3 (Supplement)

14 Personal files of enemy aliens (482). Rinaldo, Zahn. Department of Justice. Aliens Registration Branch (Archives New Zealand)

15 Andrew Francis. The enemy in our midst, 2016

16 http://www.firstworldwar.com/atoz/balloons.htm

17 Application for alien registration and change of abode notices (NAA: MT269/1, VIC/AUSTRIA/ZAHN-RINALDO JOSEPH)

18 Proceedings under the Copyright Act 1912, Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, 9 November 1922, p. 1955

19 Electoral roll for Carlton South, 1914 to 1924

20 Australian Variety Theatre Archive

21 Queensland Times, 21 May 1940, p. 2

22 The Telegraph, 20 May 1940, p. 6

23 National Security Act (1939), section 10

24 The Courier-Mail, 10 July 1946, p. 8

25 Naturalisation file of Joseph Anton Zahn Rinaldo (NAA: A714, 66/21210)

26 Biographical information sourced from birth, death and marriage records and electoral rolls.

27 Application for alien registration, op cit

Horse Drawn Cabs

Image: State Library of Victoria

Wagonettes on a cab rank in Bourke Street, near Swanston Street, circa 1880

In the 1860s and 1870s, Carlton and the northern suburbs of Melbourne were generally poorly served by public transport. There were suburban rail lines from the 1850s, but none of them ran into the northern suburbs. The first rail line to the north was opened in 1884, followed by the cable tram network in 1885. For the citizens of Carlton in the 1860s and 1870s, the only form of public transport available to them were horse drawn vehicles.

Horse drawn cabs came in different shapes and styles. For the more affluent there were 'hansom cabs', which were small vehicles shaped like a sentry box with a driver on top. These seated two people only, and were pulled by a single horse. For the less affluent there were 'Albert cars', often referred to as 'jingles'. These were two-wheeled vehicles licensed to carry six people sitting back to back. The driver and two passengers sat in the front facing the horse and three more passengers sat behind them facing the rear. 'Jingles' were not particularly comfortable as passengers were sitting over the axle and were swayed and jolted on Melbourne's rough roads, and were only partially protected from the sun and rain by an oil-cloth canopy. They were also quite difficult to get on or off, especially for ladies in voluminous dresses. 'Jingles' were soon replaced by 'wagonettes', four-wheeled vehicles in which the passengers sat in the back on two benches facing one another, with an oil-cloth hood for protection and side flaps that could be let down in bad weather. 1

Cabs did not run to a schedule along set routes, but could be hailed in the street, and would take a number of passengers who wanted to go to the same area. A passenger would hail and board a cab and state his destination, and the cabman would then drive around the streets looking for other fares who wished to go to the same place, which could be very annoying to the original hailer. A frustrated writer in The Leader newspaper wrote in 1869:

How many times have we not been induced to risk our necks by struggling up into one of these ridiculous vehicles under the delusion that "Right away Sir" meant at least some intention of starting within less than half an hour. 2

Cabmen could be fined for the practice of "duck-shoving", that is hawking a passenger about the streets at night. In March 1872, wine merchant Ludovic Marie took cabman George Hope to court for charging an excessive fare for a short trip from the city to Carlton. Mr Hope drove his passenger around the city streets for about for 20 minutes, then demanded an extra fare for going to the original destination in Carlton. Ludovic, a fiery Frenchman, took umbrage at this demand. An argument ensued and Ludovic was offloaded in the city, not far from the spot where he was picked up, minus the fare he had already paid. Ludovic had taken note of the cab's number and had some satisfaction in seeing Mr Hope fined 10 shillings, with 10 shillings costs, in the District Court. 3,4

In the city, however, there were cab ranks in which cabmen who plied to a particular suburb or district could wait for fares. We know, for example, that cabs that ran to Carlton could be picked up from the rank outside Flinders Street station, from a rank in Bourke Street near the corner of Swanston Street. This system evolved into cabs running set routes. The route to Carlton appears to have been along Swanston Street, then Lygon Street, into Elgin Street and then along Rathdowne Street. There is an account in 1877 of an accident in which a wagonette cab turned from Elgin Street into Rathdowne Street at full gallop and knocked over and killed an old lady. 5,6

Notes and References:

1 Keep, D.P., 'Melbourne's horse drawn cabs and buses', Victorian Historical Magazine, Feb-Mar 1973, p. 19-31

2 Leader, 18 September 1869, p. 18

3 The Argus, 13 March 1872, p. 5

4 Ludovic Marie lived at 333 Rathdowne Street, Carlton. He was a business partner of John Curtain.

5 The Age, 24 January 1879, p. 3

6 Leader, 13 January 1877, p. 15

The Great Race

In April 1880, the satirical magazine Melbourne Punch gave an account of a "hare and tortoise" race, in which a pedestrian outpaced a horse-drawn North Carlton cab.

But did this event actually take place as reported?

The total walking time of 54 minutes from the Kent Hotel in Rathdowne Street, North Carlton, to Bourke Street in the city sounds about right, but did Mr Tibbits really have enough time to stop off at a pub for a drink, and to visit a relative in hospital?

Conveniently, there were no independent witnesses to this remarkable event and it was not reported in any other newspapers at the time.

The slow pace of North Carlton cabmen and their propensity for taking detours were recurring themes in Melbourne Punch in the 1880s, so the "race" may well have been a belated April fool's joke.

But why let the facts get in the way of a good story?

EXCITING RACE - MAN VERSUS HORSE

A novel and interesting contest took place in one of the suburbs last Monday morning, the result of which will go far to corroborate the statements of those persons who believe that a human being is capable of more endurance than that noble animal, the horse. It is to be regretted that the struggle was an unpremeditated affair, as had it been possible to give publicity to it, it would doubtless have attracted a large crowd of the patrons of pedestrianism and the turf. Appended are particulars of the race :– It appears that Mr. Tibbits started as usual from his residence in North Carlton last Monday. At the Kent Hotel stood one of those cab-horses which have rendered the North Carlton rank famous for the speed of its cabs and the blasphemy of its patrons. "Town, sir?" said the cabman, shaking out the reins and saying, "Whoa, Emma," a perfectly unnecessary injunction to administer to his very much woebegone steed. "I just want to leave a parcel a few doors along the street," said Tibbits ; "you can pick me up as you come along." "Right, sir," said the North Carlton Cabman as he began to examine his harness, and skim the horizon with bloodshot eye in search of stray passengers. Precisely as Tibbits left his parcel and strolled townwards along Rathdowne-street, the North Carlton cab-horse started from the Kent Hotel. The man in advance was about two hundred yards ahead, but the horse was going well within itself, 33 to the minute,When Tibbits had reached the corner of Elgin and Rathdowne-streets the horse had gained considerably, not more than one hundred and fifty or sixty yards separating the man and the horse. Tibbits glanced around when he reached the corner, and seeing the cab gaining sensibly on him, he thought he would slacken off his pace, and go along the usual route to let the cab pick him up as soon as possible. When the man had reached Lygon-street the advantage was considerably in his favour, for the few customary excursions up the byestreets after imaginary passengers had thrown the horse back. Once in Lygon-street, however, the large bones, strong muscles, and superior condition of the horse began to tell in its favour. At Grattan-street the man, although not exerting himself, was scarcely fifty paces in front, but just then the horse bolted down one part of Grattan-street, as far as the University, to a man who wasn't going to town, and then up the other way to the Carlton Gardens to witness a dog-fight. This had the effect of giving the pedestrian a heavy lead; and as the horse turned into Lygon-street again, the man was just doubling the corner at the junction of that street with Queensberry-street. The cabman now put forth his undivided efforts to catch the pedestrian in time to justify the charging of threepence as fare to town.

It was 9.15 when the cab left North Carlton. The first halfmile was done in 17 minutes, and the pace now became terrific. The University Hotel was passed at 9.35, Queensberry-street at 9.41, and Madeline-street was reached at 9.46, the man still holding a good lead. The unusual pace now began to tell upon the game old North Carlton cab-horse. He knew he was overmatched, but he still struggled bravely on. The pedestrian perceiving that there was little chance of the cab overtaking him, slackened off speed, went into a public house for a drink, and called into the hospital to see how his poor relation was progressing. When he came out the cab-horse was just passing Lonsdale-street, Tibbits quickened his pace, and the cab-horse strained every nerve – a most exciting finish took place. The man and the horse raced neck and neck past the Globe, but then the breathing space which he had had, and the liquor, gave the victory to the man, for he passed into Bourke-street, hands down, several lengths in advance of the horse. The man had scarcely turned a hair. The horse showed evident signs of distress and fatigue, but persevered on to the Hobson's Bay Station. The race was most exciting, particularly at the finish. The distance was about two miles, and remembering the heavy nature of the course, and the usual speed of a North Carlton cab-horse, the time, 54 minutes, must be considered extremely fast.

Melbourne Punch, 8 April 1880, p. 3

Notes:

Madeline Street was originally the Carlton extension of Swanston Street.

The Melbourne Hospital was in Lonsdale Street, on the site now occupied by the QV Centre, and the Globe Hotel was on the north east corner of Swanston and Little Bourke Streets, Melbourne.

Horse Drawn Omnibuses

Image: State Library of Victoria

Omnibuses outside the Elizabeth Street entrance to Flinders Street railway station in the 1880s.

The omnibus on the left displays "North Carlton Rathdowne Street" signage.

A major step forward in terms of comfort and convenience was achieved in 1869 when a trio of American businessmen in Melbourne formed the Melbourne Omnibus Company and introduced an American style coach with superior suspension more suited to Melbourne's rough roads. These were brightly decorated vehicles drawn by two horses, in which passengers sat facing one another in a spacious fully enclosed cabin with glass windows and a door at the rear. The coaches were at first imported from the United States but were later manufactured by the company at its stables in Brunswick Street, Fitzroy. These horse drawn omnibuses (or 'buses for short) ran on set routes from the city to the suburbs and back to a set timetable and for a fixed fare. The first route was established by the company in 1869 and ran from the city to Collingwood and back. Other routes were soon established from Flinders Street railway station to Fitzroy, Richmond, Carlton and North Melbourne and later as far as Brunswick, Moonee Ponds, Clifton Hill and Prahran. 1

The omnibus was a popular form of public transport. The coaches were comfortable and colourful, the service was regular and reliable, and the fares were remarkably cheap. By 1881 the Melbourne Omnibus Company was operating 15 different routes into the suburbs using 178 omnibuses and 1600 horses, and carrying more than ten million urban passengers a year. One writer commented at the time that: "Nowhere do omnibuses drive a more thriving trade than in Melbourne, and they deserve it, for they are fast, clean, roomy and well managed". They made it possible and practical for residents of places like Carlton to commute to the city for work each day at a reasonable cost. 2,3

The omnibuses that ran in Melbourne in the late 19th century charged a flat-rate fee of threepence, no matter what the length of the journey. At first the fares were collected by boys who were employed to ride on the omnibuses as conductors. But these lads tended to be a bit rough and not always civil to the passengers. The company therefore did away with them and introduced a system that enabled the driver to collect the fares. Passengers deposited their threepences into a box that had an upper and lower compartment. The upper compartment had glass panels that enabled the driver to see and check the money deposited. He then pulled a lever and the money fell into the sealed lower compartment. Not everyone was happy about the loss of conductors. One Carlton resident wrote to The Herald complaining of the meanness of the company in discharging their conductors:

I have to state that they are losing daily between 50 and 60 regular passengers between Carlton and Melbourne and Melbourne and Carlton; also there are a great number of ladies who are constantly riding to town during the day, but who now take the cabs rather than be annoyed by rising up to hand money to the driver. 4

The Carlton omnibus route was the second route established by the Company in 1869, and we know that it started from the Flinders Street railway station (Elizabeth Street entrance). What route it took from there to Carlton is not clear. However we do know that in October 1886 a new route was opened to North Carlton, which ran from Flinders Street station along Elizabeth Street then via Swanston, Lygon and Elgin Streets to Rathdowne Street. It then ran along Rathdowne Street to its terminus at the corner of Rathdowne and Richardson Streets in North Carlton. 5

Not everyone was happy with the service provided by the Carlton omnibus. In August 1881, a man signing himself 'Carltonian' wrote to The Argus newspaper complaining:

There is, according to the last census, a population of close upon 40,000 in Carlton, and the omnibuses run at such long intervals, particularly in the early morning, that they are practically useless to nine-tenths of the people. I suppose there is scarcely one in ten that can catch an omnibus between the hours of half past 7 and 9am, during which time probably some 10,000 people leave their homes for businesses in the city … Fitzroy and Collingwood, which united are scarcely as large as Carlton, have no less than four different lines of omnibuses running to them, and each at short intervals, while we have only one line, and at such long intervals to be useless as a reliable means of getting to town. 6

It was always the intention of the Melbourne Omnibus Company that its horse drawn omnibuses would eventually be replaced by a more modern form of public transport that it wished to introduce from America – the cable tram. In 1885 the company began to do just that, and by 1891 it had established cable tram routes to all of Melbourne's inner ring of suburbs. In Carlton there were eventually cable trams along Lygon, Elgin, Rathdowne and Nicholson Streets. The company (now called the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company) continued to operate its horse drawn omnibuses, but as 'feeders' to a cable tram terminus from districts not directly served by the trams. This enabled the horse drawn vehicles to struggle on for a few more years. The last of the omnibus routes ran from the North Carlton cable tram terminus at the northern end of Rathdowne Street into and through East Brunswick. This route closed in May 1916 in preparation for the new electric tram route along Lygon Street, which opened in October 1916. 7

Notes and References:

1 The Argus, 7 September 1920, p. 6

2 Keep, D.P., Melbourne's horse drawn cabs and buses, Victorian Historical Magazine, Feb-Mar 1973, p. 2

3 Twopenny, R.E.N., Town Life in Australia, London, Eliot Stock, 1883

4 The Herald, 18 April 1871, p. 4

5 The Herald, 1 October 1886, p. 3

6 The Argus, 20 August 1881, p. 7

7 The Argus, 1 July 1916, p. 5

Yellow Cabs in Carlton

Image: The Argus, 15 October 1924, p. 22

In 1924 a passenger transport revolution took place on the streets of Melbourne, and Carlton played an integral role. At the time, Melbourne was serviced by taxi and car hire companies, some of them small operators with only a few vehicles. The common charging method was a credit account based on mileage from the depot to the passenger's final destination, and return to the depot after completion. The newly-formed Yellow Cabs of Australia Ltd. challenged the status quo, utilising a fleet of taxis and the latest technology from Yellow Cabs of America.

The proposed business model involved pick-up points at specific locations – hotels, dance halls and railway stations – thus eliminating the extra depot charges. There would be a centralised multi-line telephone service and call boxes linked to the nearest depot. Passengers would also be able to hail a vacant taxi directly from the street. Vehicles were to be equipped with new "taximeters" to enable passengers to monitor the fare in real time. Cash was the designated method of payment, reducing the administrative costs of maintaining credit accounts. Yellow Cabs promised a better service at a cheaper cost. Melbourne's local taxi operators were not happy about the newcomer and they took steps to protect their market share. Several operators amalgamated in July 1924 to form a new taxi company, Melbourne Motor Services Ltd.1,2

TAXI WAR

Companies AmalgamateTo meet the competition of the newly-formed Yellow Cabs of Australia Ltd., a new taxi company, known as Melbourne Motor Services Ltd., has been registered. It has a nominal capital of £500,000 (paid up to £250,000), to acquire, as going concerns, the businesses of the City Motor Service, the Melbourne Taxicab Co., and the Globe Taxi and Motor Co. The amalgamation, which is the most important move since the introduction of taxi-cabs in Australia, will lead to reduced management costs, and other economies.

The directors of the company are Messrs Walter G. Hiscock (chairman), A. E. Johns, H. A. Underwood, J. W. Proctor. Mr Henry F. McCrea, manager of City Motor Services, has been appointed general manager. The secretary is Mr L. B. Wallace. Melbourne Motor Services will control a fleet of 150 to 160 cars for private hire.

The Yellow Cab Company, which has absorbed the Royal Blue Motor Service, will have a two-story building in Elgin street, Carlton. This building, capable of housing 150 vehicles, will be ready for occupation early in October. The company will place 100 yellow cabs on the city streets about the middle of October, and the fleet will be increased. The minimum charge will be considerably below that now in operation.

Weekly Times, 12 July 1924, p. 7

Yellow Cabs of Australia Ltd. initially occupied the premises of the former Royal Blue Motor Service in Exhibition Street, but larger purpose-built premises were required to accommodate the anticipated fleet of taxis. The site chosen for the new headquarters was 100 to 116 Elgin Street, Carlton. Yellow Cabs purchased the land from the estate of George Hawkins Ievers and engaged architect Joseph Plottel to design the two storey combination garage and office. In the leadup to launch day, Yellow Cabs recruited drivers, who had to pass physical and health checks to ensure their suitability for the job, and the safety of their passengers. The drivers were to wear brown chauffeur-style uniforms, made from specially woven material.3,4,5,6

The taxis were built in Chicago – the home city of Yellow Cabs in America – and transported via Canadian National Railways to Vancouver for shipping to Australia. On arrival in Melbourne in late September, 101 taxis were assembled on the wharf and driven in a convoy to the company's headquarters in Carlton. This must have been quite a sight on the streets of Melbourne and an excellent promotion for the forthcoming taxi service. Three weeks later, on 15 October 1924, Yellow Cabs took their first paying passengers. The initial fleet was augmented with the delivery of another 51 taxis in March 1925, with the added passenger comfort of heating during the colder weather. The shareholder's meeting in July reported a net profit for the first eight months of operation to 30 June 1925. Melbourne was the trailblazer for Yellow Cabs in Australia and plans were in place to extend services to Sydney and other capital cities.7,8,9,10,11,12

During World War 2, petrol rationing and brownout restrictions had a major impact on the use of taxi services and private motor vehicles in Melbourne. The Yellow Cabs headquarters in Carlton were taken over by U.S. military authorities and the company was obliged to seek alternative accommodation in South Melbourne. This move proved to be permanent and, once again, the company had a new garage built from scratch.

YELLOW CABS LTD. SELLS GARAGE

£35,500 Carlton DealYELLOW CABS OF AUSTRALIA LTD. has sold the freehold of its large two-storeyed garage in Elgin st., Carlton, for £35,500 to E.M.F. Electric Co. Pty. Ltd., Rathdown-st., North Carlton. The Elgin-st. property was acquired by Yellow Cabs in 1925 [sic] and was used as its headquarters until it was impressed for the U.S. military authorities during the war.

Prior to this, Yellow Cabs bought a property in City-rd., South Melbourne, with a ground area of 1½ acres. Plant and rolling stock were transferred there when the Elgin-st. property was impressed. The Government permitted the company to erect temporary buildings on portion of the site so as it could carry on its operations.

When labor and materials become easier Yellow Cabs will build on the whole South Melbourne property the most modern garage in Australia. Experience has proved that the most economical working for a motor fleet is a ground floor level. The South Melbourne site will permit of this.

The Sun News-Pictorial, 16 May 1946, p. 19

Following the departure of Yellow Cabs, the former garage in Elgin Street became an equipment factory for Commonwealth Industrial Gases (C.I.G.). The building reverted to its original function as a garage and service centre in 1963, when it was acquired by the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria (R.A.C.V.). The garage was demolished and redeveloped as residential apartments in the late 1990s and early 2000s.13,14

Notes and References:

1 The Herald, 22 January 1924, p. 1

2 The Herald, 3 July 1924, p. 1

3 Certificate of Title, vol. 3593, fol. 519, 1924

4 Melbourne City Council Building Application 6472, 1924

5 Architect Joseph Plottel's work included industrial, commercial, municipal and residential building designs.

He designed the synagogue of the St Kilda Hebrew Congregation, consecrated in March 1927. (Victorian Heritage Register No. H1968)

6 The Herald, 6 September 1924, p. 82

7 The Age, 22 September 1924, p. 9

8 The Herald, 23 September 1924, p. 8

9 The Argus, 27 September 1924, p. 29

10 The Herald, 15 October 1924, p. 1

11 The Sun News-Pictorial, 28 March 1925, p. 8

12 The Age, 21 July, 1925, p. 9

13 The E.M.F. Electrical Company Pty Ltd owned the former cable tram engine house and depot on the corner of Rathdowne and Park streets, North Carlton.

14 Melbourne City Council Building Application 23799, 1946

Freeman's Livery Stables

Image: Courtesy of Peter J. Keenan

The Pram Factory (Former Freeman's Livery Stables) in Drummond Street Carlton in 1976

Many Carlton back yards would not have been large enough to acccommodate stabling for horses, and local residents and businesses often made use of commercial livery stables. In 1912 a handsome new building appeared on Drummond Street, Carlton, between Elgin and Faraday Streets, opposite the police station and just south of the courthouse. With a distinctive tower and a horse's head on the fa ade, it was the new home of Freeman's Livery Stables which had already been operating on that site for ten years in a ramshackle collection of buildings. Henry Freeman was the proprietor, but his brother Alfred was also important in the running of the business.

Designed by architect W.H. Webb, the new structure provided a large stabling area of 40 or 50 stalls and a separate space next door for coachbuilding. Upstairs at one end of the building was Freeman's hall, a large area where for the next few decades dances and meetings were frequently held. On the upper floor at the northern end of the building the design included a large and comfortable apartment for the family, with a separate entrance from the street and a brass plaque bearing the dwelling's name, Brandiston. In the 1970s the building became famous as the Pram Factory, a centre for innovative theatre for some ten years until it was sold in 1980 and demolished to make way for Lygon Court, a shopping and cinema complex.

Henry Freeman was a young man in a hurry. In 1884 at the age of 18, while operating farm machinery on a property near St Arnaud, he had suffered a disastrous accident which resulted in the amputation of fingers on his left hand. According to a family story, he was already engaged to be married but the father of his intended refused to allow the match to go ahead on the grounds that Henry would not now be able to provide adequately for a wife and family. A massive misjudgement, as it turned out. Angry and challenged, Henry returned to Collingwood where he had grown up. Within four years he had married Elizabeth Isabella Jury Clark and was running a fruit shop in Hoddle Street. Their only child, Herbert Henry Freeman, was born in 1890. In 1893 there was the first sign of what was to come when Henry briefly ran livery stables at 57 Johnston Street, Fitzroy. In the years to the end of the century he was associated with woodyards and stables in Elgin Street, between Rathdowne and Drummond Streets, and with similar businesses described as being 'off 304 Lygon Street', presumably with no street frontage. By 1902, however, his stables were permanently located in Drummond Street where the family was to trade for close to sixty years.1

The business was a very varied one. In the early days the Freemans ran horse-drawn bus services and one route was to the Warrandyte gold diggings. It was necessary to stop every seven miles to change horses, first at the Old England Hotel in Heidelberg and then at the Templestowe Hotel. Carriage building was important too. But the core of the business was the provision of stabling to many of the big businesses in the area, including Ball & Welch, a large department store in Faraday Street, as well as to smaller cab operators.

"Up to 30 carriage builders, wheelwrights, blacksmiths and stable hands were employed and many of these helped construct the building itself … Drummond Street was busy, but Freeman's Stables was the busiest point, for it was open day and night servicing the cabbies who hired their horses and hansom cabs there. It was the forerunner of a modern taxi base and, in later years, motor cars were hired as well as the wide range of horse drawn vehicles which were also made on the premises. Ernie Chandler started work as a cabbie out of Freeman's Stables in 1924, paying Alfred Freeman five shillings a day ... The horse-drawn cabs had a reprieve during the second world war when petrol rationing forced the motor cabs off the road at midnight; the horses would then take over. Bobby Patterson was a young cabbie at the time and gleefully recalls picking up the lucrative trade in stranded Yank soldiers and sailors at five pounds a head." 2

Many members of Henry Freeman's extended family were involved in the business. His son Herbert, born in 1890, completed a carriage-building apprenticeship, but he was fascinated by all things mechanical and about 1910 told his father that he was leaving the family business to became a mechanic. Famously his father replied that he was making a big mistake. 'The motor car will never replace the horse.' He was full of business confidence at this time, as is clear from his decision to rebuild, but in fact the writing was already on the wall for horse-drawn vehicles. Henry was close to his youngest brother Alfred, who had worked in the stables from the beginning and it was he who took over the business in 1923 when Henry, now a wealthy man, withdrew to concentrate on his many other interests in property and finance. By 1926, ownership of the land too had passed to Alfred but in 1928 he died and the stables were then managed by his son Albert.

By the 1930s demand for the services provided by Freeman's Stables was certainly falling and from 1935 Walter Freeman, youngest son of Alfred and brother of Albert, was operating a motor garage in the stables building. Henry, who died in 1946, was still alive to see this development. From about 1940 Walter's family occupied the apartment called Brandiston where previously his uncle Henry and then his father Alfred had lived with their families. It was large and very comfortable. The entrance was quite grand with a red carpet and a lovely timber banister. There were cornices and fireplaces and a bay window over the lane at the northern end. For the children concerned, the stables provided a wonderful playground but were not without their dangers. Heather Jones, Walter Freeman's daughter, had a nasty accident in the 1940s when she was about four and playing in the area where huge bags of chaff were stored. Her uncle Albert was feeding the chaff into a hopper, which connected to a manger in the stables below. Somehow she fell into the hopper and down into the manger, to the amazement of the horse, which reared up neighing in alarm. She had just had the first fillings to her teeth and her head was so jarred by the fall that the fillings had to be replaced. Her parents were not happy about this expense.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s the two businesses continued. When the film On the Beach (released in 1959) was being shot in Melbourne, Freemans provided the horse and driver for a scene where a car was being towed because petrol was no longer available. With demand falling, space in the building was let to other businesses and in 1939 Paramount Prams had become a tenant. Eventually its proprietor George Coulson acquired the property and in the late 1950s the death knell came when he decided to get rid of the horses. According to Albert's nephew John, his uncle, after running the stables for so many years, was heartbroken and died soon afterwards. His brother Walter expanded his garage into the stables area but by 1963 he too was dead. Another automotive business followed his but after sixty years on the site and fifty in their own building, the Freeman connection with Drummond Street was finished. Not so the building itself which shot to fame in the 1970s as the Pram Factory, the home of dynamic new theatre in Melbourne, until it was replaced in the early 1980s by the Lygon Court complex.

Notes and References:

1 1893 is the first year in which Henry appears in business directories as associated with stables. However, ESTAB. 1890 is

clearly visible on a photograph of the original stable building in Drummond Street.

2 Bill Garner in Perambulator, the Australian Performing Group newsletter, April 1980.

Related item:

Magnificent men in Flying Machines

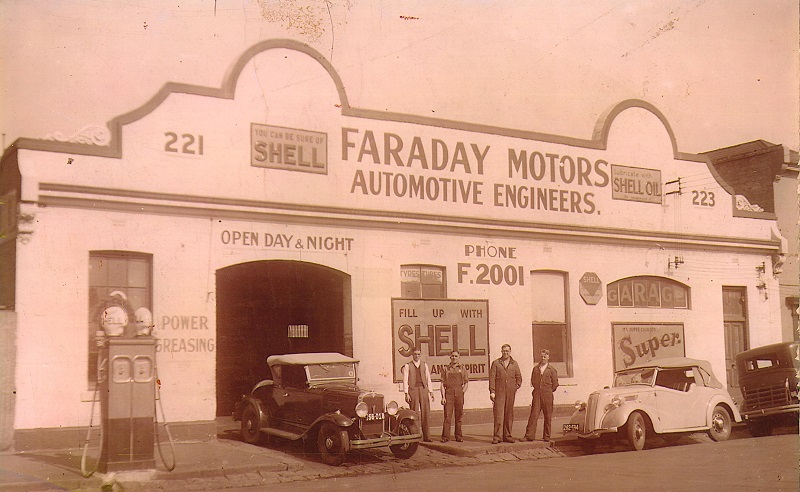

Faraday Motors

Digitised Image: Yarra Libraries

Faraday Motors, 221-223 Faraday Street, Carlton

This photograph has a date of circa 1935, but there's a clue that places the garage scene at least five years later. Vintage car enthusiasts will recognise the light coloured car as a Ford Anglia convertible. The Anglia, as the name suggests, was first manufactured in England in 1939 and introduced into the Australian market in 1940.

An Entirely New 8hp THE ENGLISH FORD "ANGLIA"

A brilliant newcomer – the Anglia, brings Ford performance, comfort, economy to the 8 h.p. field! Note the low-hung handsome lines. Step in – and experience a roominess that's new to an 8 h.p. Drive it and notice the complete appointments, experience its dashing pick-up, day-long ease of driving even on indifferent roads.STYLE IS OUTSTANDING – SO IS PERFORMANCE. Although priced with the lowest, the Anglia is built to Ford engineering standards. Body and frame are integral unit construction for extreme strength. Springbase is 99 in. for smooth riding. 4 hydraulic shock absorbers are standard equipment. The 8 h.p. engine is full of punch, yet has a petrol consumption of 45 m.p.g. and better!

HOST OF FEATURES. Including: Spare wheel and tyre in lock-up compartment – Genuine leather upholstery – Adjustable camping seat (Roadster) – Safely glass opening windscreen – Dual windscreen wipers – Glove compartment in dash – Bumpers front and rear – Tonneau Cover (Roadster) – Hood envelope – Rigid side curtains – Ventilators each side of cowl – Toolbox and complete set of tools.

See the Anglia at your local Ford Dealers. Check it against any other 8 h.p. car of similar price. Drive it. Then you'll understand what amazing value Ford has built into this brilliant new 8 h.p. car!

FORD CARS FOR 1940 – THERE'S BIGGER VALUE IN EVERY HORSE-POWER CLASS – IN EVERY PRICE RANGE

FORD MOTOR COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD. (INCORPORATED IN VICTORIA) 1

The car's six digit number plate – 282.594 – gives another clue that questions the stated date of circa 1935, as the 282.000 number sequence did not commence until November 1938. Alpha-numeric number plates were introduced in Victoria in June 1939 for new registrations and re-registrations of existing vehicles. Registration was administered by police and the new plates were initially allocated to country areas, while stocks of the old plates were still in use in the metropolitan area. This suggests that the Anglia in the photo was registered during the transition period between phasing out the old numeric plates and introducing the new alpha-numeric plates.2,3

The signage on the building façade fills in the final piece of the puzzle. The business name "Faraday Motors" first appeared in newspaper advertisements in 1937, and in Sands & MacDougall and the Melbourne telephone directory in 1938. This places the photograph in the late 1930s, but the visual evidence of the Ford Anglia suggests a starting date of 1940, during World War 2. Melbourne telephone numbers were changed in the mid-1940s, as more subscribers came on board, and February 1945 was the last year in which "F 2001" appeared in the directory for Faraday Motors. Over the next 25 years, the number was changed progressively to FJ 2001, 34 2001 and the more familiar 347 2001.4

What does this say about the date of the photo? Circa 1935 is not supported by the evidence, and the date range is almost certainly during the first half of the 1940s.

References:

1Sunday Times, 17 March 1940, p. 6

2Association of Motoring Clubs.

(The highest six digit plate number issued was 285.000.)

3The Argus, 6 June 1939, p. 11

4 Melbourne Telephone Diectory, 1938-1970

Inner Circle Railway

Image: John Thompson

North Carlton Railway Station in 1963

The Inner Circle Line was a suburban rail line completed in 1901 that ran right around Melbourne's central business district. These days, however, the name refers to the northern section of that line, a rail link that ran from Royal Park station in the west, across North Carlton and North Fitzroy to Clifton Hill station at its eastern end. This part of the inner circle line was opened in May 1888 and had three stations along the route – North Carlton, North Fitzroy and, on a short branch line, Fitzroy station. However, it was from the beginning not well patronised as using it to get to the city involved a roundabout trip through North Melbourne to Spencer Street station. There were by that stage cable tram routes available that ran more directly to the city, and which therefore took most of the patronage from these northern suburbs.

The line struggled on for several decades and was even electrified in the early 1920s to take the new electric suburban trains. But after the Second World War, passenger numbers had declined so far that it was decided to close the line. In July 1948 all regular passenger services ceased, and the stations closed. However, the station buildings at North Carlton and North Fitzroy continued to be used for a number of years as residences for railway workers and their families. The line also continued to be used intermittently by goods trains taking coal, timber and other freight to the Fitzroy station on the branch line. Passenger services were resumed briefly at the time of the Melbourne Olympic Games in 1956, when passengers were transported from Flinders Street to the Carlton football oval for Olympic events.

In the mid-1960s all of the overhead wires were removed, which meant that the only trains that could now use the line were the occasional goods trains pulled by steam or diesel locomotives. The line was used by railway enthusiasts for excursion trips. With no flashing lights or boom gates in place at street crossings, someone had to walk across the intersection to stop traffic for an approaching train. Then on 1 August 1981, the train tracks were closed, and this former section of the Inner Circle Line ceased to exist. These days the land along which it ran is a linear park and the old North Carlton station building is a thriving Neighbourhood House.

Related items:

Carlton's Forgotten Railway Line

The Inner Circle Line : The Melbourne suburban rail line that disappeared

Water, Water Everywhere!

Image: Museums Victoria

Carlton Cable Tram Stranded in Flood Waters

Chapel Street, South Yarra, 1907

Storms and flash flooding are not uncommon in the summer months. In January 1907 a Carlton-bound cable tram was stranded in flood waters in Chapel Street, South Yarra, miles away from its destination suburb. Passengers had to leave the tram and wade through the water to make their way to higher ground. Even when the flood waters subsided, the tram service would not have been restored immediately. The stormwater from overflowing drains carried all sorts of debris and this would have to be cleaned out of the slot that carried the cable, which moved the tram.1

The St Kilda (Brighton Road) to Carlton tram route travelled along Chapel Street, Toorak Road, Park Street, Domain Road, St Kilda Road and Madeline (Swanston) Street. The line was closed in 1925.

1 The Argus, 26 January 1907, p. 19

Digital Image: State Library of Victoria Dummy Car (right) and Trailer in Lonsdale Street Melbourne Heading to North Carlton via Lygon, Elgin and Rathdowne Streets  Photo: CCHG Former Cable Tram Engine House Corner of Rathdowne and Park Streets North Carlton  Photo: CCHG Site of Former North Carlton Cable Tram Route Rathdowne Street North Carlton

Notes and References: |

The Perils of Tram TravelAugust 2016 marks the 80th anniversary of the last cable tram to run along Rathdowne Street, North Carlton. The North Carlton route from Elgin Street to Park Street, opened on 9 February 1889, was a relative latecomer to Melbourne's cable tram network. Melbourne commenced its first cable tram service to Richmond in 1885, and services along Nicholson Street to Park Street, and Carlton via Lygon and Elgin Streets were introduced on 30 August and 21 December 1887. Lygon Street north of Elgin Street was not part of the cable tram network and had to wait until October 1916 for an electric tram service. 1,2 Cable trams revolutionalised public transport and enabled large numbers of passengers to travel at an affordable cost. But, like any innovation, tram travel was not without its problems. Road users people crossing the street, children at play, cyclists, hand carts and horse drawn vehicles had to make way for a larger and more powerful beast. Inevitably, there were accidents, some fatal, and The Advocate reported in June 1887: "By tram accidents no less than six persons have lost their lives and twenty-three been injured in less than two years." 3 Carlton had its fair share of mishaps on the streets serviced by cable trams. Carlton's first tram fatality occurred on the evening of 24 April 1888, when a nine year old boy named Thomas Stewart was caught underneath a dummy car in Lygon Street. The boy, who lived with his parents in Union Place, Carlton, died soon after arrival at Melbourne Hospital. Children were, unfortunately, often casualties of tram accidents. Two young children playing in Lygon Street were injured in July 1890. They had moved out of the way to avoid an oncoming tram, but were hit by another travelling in the opposite direction. In October 1927, Victor Stobaus, aged seven years, had his foot badly crushed when it was caught under the wheel of a tram in Rathdowne Street near Newry Street. The foot was later amputated, but young Victor's disability not prevent him from becoming a talented footballer in the Melbourne Boys' League. Victor's father, Robert Stobaus, made an unsuccessful claim for £499 damages against the Tramways Board in the County Court in July 1928. 4,5,6 Saturday 25 April 1914 was a particularly bad day for tram accidents in Carlton. In the morning, Walter England, a clerk at the Carlton Court, fell from a moving tram in Carlton and was dragged some distance along the road. Mr. England suffered injuries to his ribs and hip and was admitted to the Melbourne Hospital for treatment. That afternoon, a more serious accident took place near the corner of Grattan and Lygon Streets. John Griffiths, a 26 year old tutor at the University High School, was crossing the road behind a north-bound tram when he was struck by another tram travelling towards the city. Mr. Griffiths was pinned beneath the dummy of the tram, which had to be lifted off the rails before he could be extricated. He was taken to the Melbourne Hospital, suffering from a compound fracture of the leg, extensive abrasions, and shock. 7 Tram passengers were also at risk in the old open-style tram cars. Sarah Dicker, a young woman who worked at Mrs Garland's fancy goods shop in Drummond Street, had a fainting fit and fell from a tram onto the road in Elgin Street in December 1890. She suffered head and facial injuries. Charles W. Jonah, aged 76, of Union Place, Carlton failed to heed the tram gripman's warning of "mind the curve" and fell from a tram as it turned the corner from Rathdown Street into Elgin Street in July 1924. Mr Jonah was admitted to hospital and discharged after treatment. 8,9 Of all the tram accidents reported, possibly the most tragic occurred in April 1919, while a tram car was being shunted at the sheds in Nicholson Street, North Fitzroy. Tram gripman Victor Cocking, who lived nearby in Canning Street, North Carlton, was entering Nicholson Street from Mary Street when he saw a child fall off the back of a dummy car. He rushed across Nicholson Street but he did not know, until he picked up the child's body, that it was his own son, John Cocking. The boy, aged six years, died later that evening in the Children's Hospital. 10 Cable trams had their heyday in the 19th century, but lasted only a few decades into the 20th century. The cable tram network was phased out from the 1920s through to 1940 in favour of electric trams, which promised a more efficient service and better carrying capacity. Lygon Street already had an electric tram service, dating back to 1916, north of Elgin Street. The Carlton, North Carlton and Nicholson Street cable tram routes were replaced with motor buses. When the North Carlton route closed on 2 August 1936, both the tram car and crew were besieged by souvenir hunters, seeking a piece of memorabilia. Three years later, when the Carlton route closed in April 1939, the Tramways Board foiled an alleged plot by hoodlums to seize the last tram and push it into the Yarra River. They had learnt from previous acts of vandalism and employed the simple strategy of substituting motor buses on the last night of service. Melbourne's last cable tram ride was from Bourke Street in the city to Northcote on the evening of 26 October 1940. Services via Nicholson Street to East Brunswick were later restored with electric trams in 1956. 11,12,13 Melbourne's electric tram network, one of the largest in the world, survived threats of closure in the mid-20th century and has continued to grow into the 21st century. The dangerous days when tram passengers travelled on running boards, or by hanging out of open doorways, have gone and many safety features have been incorporated into modern tram design. But accidents can still happen. In May 2016, a tram was derailed and crashed into a house in High Street, Kew, when a car travelling in the opposite direction strayed onto the tram tracks. Two months later in July 2016, a horse drawing a tourist carriage crashed its head through the driver's window of a tram in Swanston Street in the city. As expected, the horse came off second best to the larger and more powerful beast, but was not seriously injured. 14,15 Related Item: The Cable Trams of Rathdowne Street |

The Electric Trams of Lygon Street

On the last day of October each year, children, some dressed in ghoulish costumes, take to the streets and celebrate the time-honoured tradition of Halloween. In 2016, local residents had even more reason to celebrate, as 31 October marked the centenary of the first electric tram service along Lygon Street. Lygon Street originally had a cable tram service, dating back to December 1887, as far as Elgin Street, but passengers wishing to travel further north had to offload and catch a horse-drawn omnibus. Nicholson Street and Rathdowne Street had cable trams north of Elgin Street, so why should Lygon Street have a "an antiquated bus service which is believed to be identical with the one that conveys visitors to the Ark up to the top of Mount Ararat?" 1

The impetus for an electric tram service came from the northern suburbs of Brunswick and Coburg, which had grown in population in recent years, creating a demand for improved transport. At a meeting of the Brunswick Council on Monday 13 June 1910, Mr R. Kyrle, Secretary of the North Brunswick Progress Association, proposed a scheme of running an electric tram line along Lygon Street and Holmes Street to the Coburg Cemetery. This was taken up by the East Brunswick Tramway League in February 1911 and followed up by a series of meetings with residents and ratepayers of Brunswick, Coburg and North Carlton later in the year. The proposal received enthusiastic support, but its successful implementation was dependent on co-operation and cost-sharing between the three municipalities of Brunswick, Coburg and Melbourne (representing Carlton and North Carlton). There was a precedent for this scenario in the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust, which had operated electric tram services from May 1910 and was now returning a profit. The proposed Lygon Street line would be about 4½ miles (7¼ km) long from Elgin Street, Carlton to Coburg, at an estimated total cost of £80,000, compared to the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust cost of £90,000. The cost-effectiveness of running trams from Elgin Street to Park Street was questioned because the section between Princes and Macpherson Streets was occupied on the western side by the Melbourne General Cemetery, whose residents had no further need of transport. An alternative route of running electric trams down Park Street to connect with the Rathdowne Street and Nicholson Street cable tram routes was considered and rejected, as it would it would be of no benefit to the residents of Princes Hill (North Carlton) and would contribute to overcrowding on the existing cable tram lines. Eventually, the tram routes and administrative arrangements were sorted out, but Lygon Street had to wait another five years for its electric tram service. 2,3,4,5,6,7

In February 1914, the Brunswick & Coburg Tramways Trust was established to construct and operate an electric tramway from North Carlton to Brunswick and Coburg. Later that year, in October 1914, the Trust was re-constituted as the Melbourne, Brunswick & Coburg Tramways Trust, reflecting Melbourne City Council's involvement. The much-anticipated Lygon Street electric tram service was opened in two stages in 1916, with an extension of the Coburg line from Moreland Road to Park Street via Lygon Street opened on 14 August, and a further extension from Park Street to Queensberry Street, via Lygon Street, Elgin Street and Madeline (Swanston) Street on 31 October. Residents of Carlton and North Carlton had a preview of the tram service the day before, when members of the Trust went on a trial run before the official opening. On the afternoon of Tuesday 31 October 1916, under threat of a storm typical of Melbourne's spring weather, six electric trams, officials and curious onlookers assembled at the corner of Madeline and Queensberry Streets. Care was taken to ensure that all parties were represented in the ceremony and the ladies, no doubt, had some assistance from tramways staff. After introductory speeches, Lady Hennessey, wife of Melbourne Lord Mayor David Hennessey, cut the blue ribbon spanning the track and proceeded to drive the leading tram, followed by Mrs Reynolds, wife of the Chairman of the Tramways Trust, driving the second tram. The tram procession continued along Madeline, Elgin and Lygon Streets to Park Street, where a second ribbon cutting ceremony took place. Mrs Phillips, Mayoress of Brunswick, took charge of the leading tram and travelled through Brunswick to Moreland Road, the boundary line between Brunswick and Coburg. Mrs Richards, Mayoress of Coburg, then cut another blue ribbon and took over for the final leg of the journey to Bakers Road, Coburg. 8,9

Unlike cable trams, which were drawn along by a continuous below-ground cable, electric trams were powered by electricity via a network of overhead wires. Any interruption to the power supply, whether from a substation outage, damage to overhead wires or loss of connection between the trolley pole and the wires, brought the tram to a stop. A tram taking a corner at speed could lose its trolley pole connection and another could get stuck at a "cut off" point, which marked the change from one power supply to another. Electric trams could travel at a higher speed than the old cable trams and they had a different braking system. There was a spectacular incident in Carlton in July 1925, when the dynamo of an electric tram fused, disabling the air brakes and sending the tram hurtling along Lygon Street at a speed of thirty miles an hour. The tram continued out of control up Elgin Street to Madeline Street, where the driver was finally able to apply the emergency brakes and bring the vehicle to a shuddering stop. Neither the driver, nor the passengers on board, were injured, but the incident was a cautionary tale of the immense power of an electric tram, compared to a cable tram or horse drawn omnibus. 10

In the first twelve months of operation, the Lygon Street tram service had the dubious honour of a suicide. On the afternoon of 7 June 1917, Hector Henry Porter, aged 63 years, was seen wandering across the tram tracks in Lygon Street, North Carlton, near Paterson Street. He stepped in front of a city-bound tram, in what appeared to be a deliberate act of suicide, and suffered fatal injuries. At the inquest held a week later, the coroner Robert Hodgson Cole found that Porter died by his own act and had shown signs of mental unsoundness at the time. He cleared the tram driver, Ernest William Hoare, of any blame for the death. A few years later, in February 1920, a cyclist died in a shocking accident in Lygon Street near Curtain Street, North Carlton. The cyclist was riding along the tram tracks when he was first hit by a city-bound tram, which then propelled him into the path of another tram travelling north. The man, thought to be named Harvey, was identified only by a numbered Wharf Laborers' Union badge he was wearing. 11,12

The Lygon Street tram service remained under the control of the Melbourne, Brunswick & Coburg Tramways Trust for five years only until the end of 1919. In November of that year, the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board (MMTB) was established to operate the entire tram system in Melbourne. The Melbourne, Brunswick & Coburg Tramways Trust, along with four other municipal tramways and the private Northcote cable line, came under the control of MMTB on 2 February 1920. The decision was not popular amongst some local council officials, who considered they were better placed to operate their own tram services. The Board's original plan to replace existing cable and horse drawn services with electric trams proved to be unachievable on such a large scale. The cable tram network had reached the end of its useful life and was progressively shut down, with some routes converted to electric traction and others replaced by motor buses. This was the fate of the North Carlton route along Rathdowne Street, closed in August 1936, and the Carlton route along Lygon and Elgin Streets in April 1939. The Nicholson Street route was closed in October 1940 and temporarily replaced by motor buses, but services to East Brunswick were later restored with electric trams in 1956. 13,14,15,16,17

The Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board continued until 1983, when an integrated tram, rail and bus network was created under the control of the Metropolitan Transit Authority. For the first time ever, the travelling public could transfer from one service to another on the same ticketing system. The 1990s saw major political and administrative changes, with the privatisation of public transport and other state-owned utilities. In a short-lived (some might say ill-fated) move, tram services were split between two independent operators, Swanston Trams and Yarra Trams, in August 1999. This arrangement proved unsustainable, as Swanston Trams (re-branded as M>Tram) failed to meet its performance targets and withdrew from the contract in December 2002. Yarra Trams assumed control of the entire tram network in April 2004 and continues to operate services to this day. Trams have become larger and more complex in operation, but the basic tram infrastructure of metal tracks and overhead wires is essentially the same as it was on that spring day in 1916, when the first electric tram travelled along Lygon Street.18

Notes and References:

1 Coburg Leader, 17 February 1911, p. 1

2 Coburg Leader, 17 June 1910, p. 4

3 Reuben Kyrle (Keirl) was a colourful character.

In April 1906, he appeared in Carlton Court as defendant in a maintenance case involving his wife Elizabeth and in 1915 he was "deported" from Tasmania for impersonating a transport officer.

4 Coburg Leader, 17 February 1911, p. 1

5 Coburg Leader, 21 July 1911, p. 4

6 Coburg Leader, 1 September 1911, p. 4

7 Coburg Leader, 15 September 1911, p. 4

8 A brief history of the Melbourne, Brunswick and Coburg Tramways Trust. Tramways Publications, 1999, p. 1

9 Brunswick and Coburg Leader, 3 November 1916, p. 2

10 The Age, 17 July 1925, p. 13

11 Inquest 1917/482, 14 June 1917

12 The Age, 25 February 1920, p. 10

13 The Argus, 28 October 1919, p. 6

14 The Argus, 3 August 1936, p. 8

15 The Argus, 18 April 1939, p. 11

16 The Argus, 28 October 1940, p. 2

17 The Argus, 6 April 1956, p. 5

18 Yarra Trams Website

Last Tram Out of the Depot

Photo: CCHG

W7 class tram no. 1031 in prepartion for its final run out of the former tram depot in Nicholson Street.

The cranes on the right hand side were used to lift the tram onto the back of an over size load truck.

Friday 23 August 2024 marked the end of an era for W class trams in Nicholson Street, North Carlton and North Fitzroy. W7 class tram no. 1031 was the last of six W and SW class trams to be removed from the former North Fitzroy tram depot, where they had been in storage since 2014. The depot, now home to the bus company Kinetic, serviced the Nicholson Street tram route from 1956, when electric-powered trams replaced buses on the Bourke Street to East Brunswick run. 1956 was also the first year that tram no. 1031 came into service. However, the history of trams in Nicholson Street goes back as far as 1887.1

The Nicholson Street cable tram service opened in 1887 and was the first to operate in Carlton. The introduction of affordable public transport was a boon to residents and businesses on both sides of Nicholson Street, and facilitated development of the shopping precinct as far as Park Street, North Carlton. The cable trams served their purpose for decades, but they were considered an inefficient mode of transport into the 20th century. The Nicholson Street cable trams were replaced by buses in October 1940. London-style double deck buses operated for a time, but they proved inefficient at peak hour and were phased out. The service was restored with electric-powered trams in April 1956 and, with major upgrades in infrastructure and rolling stock, continues to this very day. The tram tracks leading into the depot are still visible, but a short section connecting to the main line in Nicholson Street was removed in January 2020, when the tram tracks were dug up and re-instated during installation of new accessible tram stops.2

View video clip of W7 class tram 1031 leaving the North Fitzroy depot on Friday 23 August 2024.

Notes and References:

1 https://vicsig.net/index.php?page=trams§ion=heritage&museum=north%20fitzroy

2 Jones, Russell. No stairway to heaven : the failure of double deck buses in Melbourne. Melbourne Tram Museum, 2017